As mentioned in a previous blogpost the biggest roadblock to encourage more girls into STEM is not knowing about the women who came before them. I certainly wish I grew up knowing who these incredible women were and the remarkable achievements they made. We have compiled a history of as many females who have made an impact on our lives even today without stepping on the toes of the incredible authors who have already compiled books on the subject which you can see here.

These achievements were not all one-sided because a lot of these women you are about to meet worked alongside their male colleagues, family members and mentors despite the deep gender inequalities in the workplace that laid the foundations of women’s suffrage movements across the globe. The women who stepped up to the place to become the original STEMETTES enjoyed their scientific work immensely as there was parity between the genders on an intellectual basis.

2300 BCE

En’Hedu’anna, Priestess of Ur, studied astronomy tracking moon cycles recording them as poetry which were recited for 500 years after her death.

3rd Century BCE

Merit Ptah was the Chief physician of Ancient Egyptian Pharaoh’s court. In traditional oral histories she was reportedly the first ever woman in medicine recorded.

10th Century

Syria: Al-Ijliya Al-Astrulabi invented the astrolabe.

18th Century

Born in 1723 in Luxembourg Palace, Paris, France Lepautre was a French mathematician and astronomer. Her family worked as part of the Spanish Royal Household staff where her father, Jean Etable, was a valet.

In 1749 aged 26 Nicole-Reine married a royal clockmaker Jean-Andre Lepautre and together with Nicole spurred on by her husband’s encouragement they made a clock with astronomical component inside.

In 1853 Nicole and Jean-Andre full of pride at their creation decided they wanted to share it with the scientific community and took it to the French Academy of Science to showcase to its committee. Jerome Lalande impressed by the workmanship involved in making the clock examined and endorsed it. He then sponsored Nicole-Reine to work in a team alongside mathematician Alexis Clairault at his request. Predicted Halley’s Comet’s return by calculating how long the solar eclipse would take. They worked on the predictions for 6 months and theorized that the comet would arrive on 13th April 1759 instead it arrived exactly a month earlier than predicted.

To Lalande’s dismay, Clairault made no effort to acknowledge Lepautre’s work or the influence the role she had on his which Lalande was upset by and later endorsed the impact Lepautre had on the project in an article he wrote. Though nothing could make up for the hurt it caused Lalande and Lepautre, Lalande employed Lepautre again to work in his own team calculating the ephemeris that charted Venus’ travels between the sun and any planet that swamped it in size.

In 1761 Nicole-Reine was inducted into Scientific Academy of Beziers as an honorary member. Not long after Lalande and Lepautre co-wrote the astronomer and navigator annual guides for the Academy of Science together.

In 1762 Lepautre correctly identified there would be a solar eclipse on 1st April 1764 detailing in 15-minute periods on a map as it travelled across Europe. Lepautre wrote an article on the occasion published by ‘Connaissance des temps’ (Knowledge of time).

Sadly, for the next 11 years Nicole-Reine spent much of her time in between her studies caring for her terminally ill husband Jean-Andre until her own death in 1788. Determined to make the most of the rest of the time they had together, in 1767 she adopted Jean-Andre’s nephew Joseph Lepautre Dagelet. Dagelet himself later became a member of the French Academy of Science.

Between 1774-84 Nicole-Reine catalogued stars in groups useful for astronomers to use in the future calculating the planetary and lunar travels in the Milky Way.

Lalande wrote a brief biography of Lepautre after her death in 1788 about the astronomical contributions. She was posthumously honored with 7720 Lepaute asteroid and the Lepautre lunar crater.

19th Century

The turn of the century brought more women into STEM fields because of education with the infamous ‘7 Sister Colleges’ where women could attend college and pursue their dreams. A new option to study computer science courses became available to women who knew nothing about the subject.

The Seven Sisters were: Barnard, Bryn Mawr, Mount Holyoke, Radcliffe, Smith, Vassar and Wellesley. This could not have happen without the passing of Title IX of the Education Amendment into law whose purpose was to encouraging women to take up STEM-related subjects. It thus made it illegal for schools and study programs funded by the federal government to bar women from being educated because of their gender.

After the women had finished their college education they were further encouraged into teaching jobs to spread the knowledge and encourage more women and girls into the field. Although this was not always what they had signed up for it was a means for them to live independently.

Unlike today, where the world of work is changing to sustain and retain women who want the best of both worlds (work and home) in the 1800s female faculty staff were forced to resign if they got married. A career and a marriage was simply not an option and the jobs they had meant they kept unsociable hours so it’s perhaps understandable that many women did not marry nor have children.

Ada Lovelace

Born December 10th 1815, London to Anne Isabella Noel Byron and the lothario poet Lord Byron. She is well known as the world’s first computer programmer.

Ada spent much of her childhood being home-schooled by her mother on an educational feast of STEM subjects instead of the more artistic subjects like literature, art and reading. . Anna feared the very thought of Ada following in her incestuous father’s footsteps because she didn't want her daughter to be as mad as her father.

Ada’s ability to analyze numbers meant that she often experienced severe migraines impacting her vision. It took Ada a long time for her to find her supporters and mentors because her male counterparts were convinced that mathematics was too complicated for a woman. Ada vehemently disagreed with the sentiment instead gave her STEM subjects credit for keeping her sane.

By the age of 23, Lovelace was married and already had three children. Her husband encouraged her to go and help her mentor and great friend Charles Babbage on ‘The Analytical Machine’. This explained the concept of a specific engine could transition calculation to computation.

Ada’s next major piece of work was translating lecture notes written by Luigi Meneabrea, an Italian engineer on the topic of Charles Babbage’s Analytical Engine called “Notions sur la machine analytique de M. Charles Babbage”. She found it full of mistakes and took the time to correct them in the footnotes she made in a book she aptly titled “Notes”.

The contribution Ada made wasn’t formally recognized until 1950s by B.V Bowden who republished Lovelace’s notes ‘Faster than Thought: A Symposium on Digital Computing Machines’.

Even today Lovelace’s name is known the world over and the legacy of what she left means that every 2nd Tuesday of October celebrates Lovelace’s life to raise awareness of women in STEM and showcases the impact of them as role models.

Maria Mitchell

Born in 1818 in Nantucket, Massachusetts, Mitchell was a STEM advocate for women and girls and the very first female astronomy professor in all of America.

Mitchell’s parents were Quakers who advocated equal education for women and girls and her father was an astronomer and teacher who also actively contributed to his daughter’s science education.

Attended Cyrus Peirce’s School for Young Ladies where she completed her education at 16 and opened a school to train girls in mathematics and science.

In 1836 Mitchell was a librarian at the Nantucket Atheneum for two decades and spent her days reading. At night-time she was with her father who was principal officer of the observatory he built on top of Pacific Bank. It was here that Mitchell filled her mind, world and boots with astronomy when he let her assist in his work of rating chronometers for Nantucket whaling fleet and actively encouraged independent use of his telescope.

October 1st 1847 aged 29 Mitchell was the first American scientist to discover a comet. This astronomical breakthrough earned her the gold medal from King Frederick VI of Denmark. The following year she was the first elected woman at the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, the American Association for Advancement of Science and the American Philosophical Society. She was also one of the first women employed by the US government to make calculations for a project conducted by US Coastal Survey.

By 1856 Mitchell had learned all that America had to offer her so she left the Atheneum and travelled around Europe meeting fellow astronomers. The impact these new experiences had on Mitchell had become all too clear from not just a scientific standpoint but a civil one too. When she returned to America she spent 1857 to 1858 involved in the anti-slavery and suffrage movements.

By 1861 Mitchell moved back in with her widowed ailing father in Lynn, Massachusetts.

Post-Civil War, Matthew Vassar (founder of Vassar Woman College, Poughkeepsie, New York) employed Mitchell at the faculty giving her access to a 12-inch telescope then the third-largest in America allowing her to specialize in Jupiter and Saturn’s surfaces. At first Mitchell was reluctant and had to be encouraged to take up the post by her father.

In her new job at Vassar, Mitchell created pioneering daily photographs of sunspots and discovered whirling vertical cavities instead of clouds as previously thought. Studied comets, nebulae, double stars, solar eclipses and Saturn and Jupiter’s elements.

Mitchell defied social conventions by inviting female students out at night just as her father had done for her. This was predominantly for class work, celestial observations and where prominent feminists like Julia Ward Howe had been booked to speak on the female suffrage issues of the day. In these classes sat her star students Christine Ladd-Franklin and Ellen Swallow-Richards. The research compiled by Mitchell and her students was routinely published in academic journals which up until then only featured men. In 1906, 3 of her future female proteges were listed in the first list of Academic Men of Science.

In 1869 Mitchell was elected to American Philosophical Society and co-founded American Association for the Advancement of Women (AAW) later renamed as American Association of University Women. Mitchell served as its 1873 President. She was also elected vice president of the American Social Science Association which was a historic moment for women in an organization that then included a mixture of both men and women for the first time.

In 1876 celebrating the centennial year of America’s birth, Mitchell gave a speech on ‘The Need for Women in Science’. Who knew that 145 years later we’d still be talking about such an important topic? What would Mitchell think about this all these years later?

In 1888 Mitchell entered retirement from Vassar College but continued researching in Lynn, Massachusetts close to where her sister lived. She died a year later.

In 1902 still much loved and respected after her death by friends and supporters, they founded Maria Mitchell Association in Nantucket and preserved her home which is still open to visitors. Three years later, Mitchell was posthumously inducted to the Hall of Fame of Great Americans and only 1 of 3 women bestowed with the honor. She was also inducted into National Women’s Hall of Fame in Seneca Falls, New York. When astronomers first landed on the moon over 60 years later, they honored Maria Mitchell by naming one of the Moon’s lunar craters after her.

Born in 1821 in Bristol, United Kingdom with both parents heavily involved in civil causes. At the age of 11 Elizabeth and her family moved to Boston, America for financial reasons and to do their bit in abolishing slavery. Unlike her contemporaries Elizabeth not drawn to science nor the field of medicine instead she preferred reading and writing subjects that became the stereotype for women to be pushed into later on.

In 1838 Samuel Blackwell Sr. died but his children carried on his fight for women’s rights and protested in favor of abolishing the slave trade.

She became a physician when a dying female friend told her that things might have been different if she had had a female physician. She spoke to all the family physicians who supported the idea but warned her that it was impossible, too expensive not to mention medical education had not been made available to females. Convinced there was some way to achieve this, Blackwell persuaded 2 physician friends to join them in their medical studies and then applied to all medical schools in New York and Philadelphia and 12 schools in the north-east states.

There are records stating that the all-male student body jokingly admitted her in a vote held by the faculty and she went to Geneva Medical College. This joke was on her male colleagues whose mistake enable Blackwell to become the first woman in America to earn her doctorate in medicine upon graduating New York’s Geneva Medical College in 1849.

For 2 years, she worked in London and at a Parisian clinic ‘La Maternite’ studying midwifery where she caught “purulent opthalmia” from one of her patients causing her to lose her sight in one eye. By 1851, Blackwell returned to NYC and forced to give up a surgeon career. Instead she set up her own clinical practice but did not have many other physicians working alongside her and saw even fewer patients. She closed down her practice and applied to be the physician in the women’s department at a large dispensary in the city. Sadly Blackwell got rejected but she was not dejected instead she saw the opportunity to help other women with a dispensary of her own.

In 1853 Blackwell opened her own clinic in a single rented room only seeing 3 patients a week. A year later, Blackwell transformed her clinic into an incorporation moved the business premises to a small house on 15th street. In 1856, Elizabeth’s doctor sister Emily joined the then family business and was later joined by family friend Dr. Marie Zakrzewska. By 1857, the premises had become so successful that the three women had to move the premises again to 64 Bleecker Street where they opened the New York Infirmary for Women and Children. Now the dream was bigger than any of the women had ever thought but their desire to improve the situation for fellow females was still just as strong.

Inside the New York Infirmary for Women and Children they provided training and experience for female doctors as well as offering care to the poor and their families. Blackwell championed medical education and careers for all women offering practical help to women who were refused any experience in the medical sphere and keen to teach useful skills needed to become a physician.

When it came to writing she published works including ‘Medicine as a Profession for Women’ (1860) and ‘Address on the Medical Education of Women’ (1864). In 1895 Dr Blackwell wrote in her autobiography ‘Work in Opening the Medical Profession of Women’ where she spoke of her initial disgust at studying medicine repulsed of all that was connected to the body. She didn’t like medical textbooks instead she professed a love for history and metaphysics.

With her health declining, Blackwell retired from practicing medicine in the 1870s but continued campaigning for health reforms in particular pertaining to female health. She died in 1910.

Born December 3rd 1842 in Dunstable, Massachusetts who became a chemist and American Movement Home Economics Founder. Richards was home-schooled for much of her young life but she did attended Westford Academy where she trained as a chemist and later taught there.

In 1870 Richards graduated with a Bachelor of Arts degree from Vassar College and in 1873 was the first woman to be admitted to the infamous Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) to study a Bachelor of Science. Richards had her master’s thesis accepted at Vassar College. Though she stayed on at MIT to continue her graduate studies she could not be awarded a PhD because female PhD students were not recognized.

In 1875, Ellen Swallow married Robert Hallowell Richards, a mining and metallurgy expert at MIT. Keen to further the cause of females in science Richards persuaded the Women’s Education Association of Boston to contribute financial support towards Women’s Laboratory at MIT. With Professor John M. Ordway, Assistant Director MIT’s Women’s Laboratory, she started working on encouraging women into STEM with training opportunities for suitable candidates.

Chemistry, Biology and Mineralogy courses were taught and thanks to Ordway’s network connections the women were able to obtain government work contracts.

Richards then became Head of Science section at the Society to Encourage Studies at Home. In 1881 Richards co-founded Association of Collegiate Alumnae with Alice Freeman Palmer later renamed American Association of University Women. Sadly in 1883 the Women’s Laboratory closed despite MIT regularly admitting its high achieving students. It’s unclear why this happened but most likely to do with a lack of funding or a decision made by the board of trustees.

In 1884 Richards carried on her working career despite her marriage and took up an assistant post to Professor William R. Nichols at the institute’s new sanitation chemistry laboratory. She held the instructor post for the rest of her life.

Between 1887-89 Richard oversaw laboratory work for Massachusetts State Board of Health’s survey of inland waters.

In 1890 Under Richards’ watch, the New England Kitchen opened in Boston offering nutritious food to working class families at low cost whilst teaching the scientific methods they used. Four years later New England Kitchen signed an agreement where they provided Boston School Committee school lunches. Richards lobbied for Home Economics courses to be taught at all Boston public schools.

In 1897 Richard helped Mary M.K. Kehew organize a housekeeping school in the Woman’s Educational and Industrial Union which later became a part of Simmons College. By 1899, the word had spread about her housekeeping school and home economics course that Richards held a summer conference for workers at Lake Placid, New York. As Chairman and overseer of the conferences, they established the standards, planned courses, study guides and bibliographies for what later grew into Home Economics. The movement had grown so much across the country that by December 1908 the conferees formed the American Home Economics Association and had Richards duly elected their first ever President holding the post until 1910 until her retirement. In the last two years of her phenomenal career, she created AHEA’s ‘Journal of Home Economics’ and Appointed responsible for managing home economics curriculum in public schools by the National Education Association.

Richards died March 30th 1911.

Her published works include: ‘The Chemistry of Cooking and Cleaning’ (1882; with Marion Talbot); ‘Food Materials and Their Adulterations’ (1885); ‘Home Sanitation: A Manual For Housekeepers’ (1887); Domestic Economy as a Factor in Public Education’ (1889); ‘The Cost of Living’ (1899); ‘Sanitation in Daily Life (1907); Euthenics: The Science of Controllable Environment (1912).

Born December 1st 1847 in Windsor, Connecticut and became a noted psychologist, logician and mathematician. Her biggest contribution to science was color vision theory.

Both of Ladd-Franklin’s parents came from distinguished families with her father as a merchant and mother was 1 of 4 girls and a feminist. Greatness was inherited in the Ladd family with William Ladd, a great uncle, founded the American Peace Society which was made up of Christian pacifists in Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire and New York. Another great uncle was a Connecticut senator and United States Postmaster General under Martin Van Buren and 6 maternal ancestors were members of Constitutional Convention of the Colony of Connecticut. This encouraged Christine to use her intellect and connections to pursue a career in STEM and when she heard Vassar College had been built it was the first place she wanted to continue her studies.

In 1859 her mother, Augusta Niles Ladd, died of pneumonia and Ladd-Franklin was sent off to live with her paternal grandmother in Portsmouth, New Hampshire. There she attended the Wesleyan Academy in Wilbraham, Massachusetts and did the exact same course as the males who aimed to get into Harvard.

Ladd started keeping a diary in 1860 continuing to write in one until at least 1873 when she lambasted the idea of keeping a diary.

In 1865 Ladd-Franklin graduates as class valedictorian from Wesleyan Academy. A year later she persuaded her grandmother that to support herself with a job she needed to continue her education. Her grandmother agreed and duly informed her granddaughter to speak to her aunt Juliet Niles about supporting her endeavors in a financial capacity. With her aunt onboard with the idea Ladd enrolled in Vassar’s second class since it opened.

When she got there it appeared not all as she had hoped it would be. There wasn’t anyone who would debate with her and no female at the college was interested in pursuing female rights. Instead she spent a lot of time being outspoken against Confederate sympathies.

She was there to study and so signed up for Latin, Trigonometry, French, Geology and Music and though good at all subjects especially so in Geology and wrote excellent essays, she often referred to herself as the class dunce. She promised herself that she would dedicate more time to her studies which paid off when her teacher and corridor teacher Miss Clarke complimented her on her work. She wrote home the following week requesting to stay on for another 2 years but had to leave at the end of the academic year.

She started her teaching career of German, Music and reading at Utica, New York. She enjoyed her teaching career but experienced a personality clash with Miss Backus the other schoolteacher. In April 1868 The Hartford Courant published her translation of “Des Mädchens Klage” and as a passionate botanist collected 150 plant species.

With her aunt’s financial help, Ladd returned to Vassar and started writing her diary in German and French. She performed a Physics demonstration and another in astronomy in front of Maria Mitchell. Ladd-Franklin took up Greek and challenged herself to read and recite Sophocles’ Antigone. She started writing for ‘The Transcript’ Vassar’s student newspaper. On October 24th despite her feeling at home in astronomy Ladd was unable to report Venus related observations with her classmate Lizzie Coffin. Yet one month later Ladd-Franklin was promoted in her astronomy class. In 1869 as Vassar College Philalethean Society’s Beta Chapter President, Ladd was bestowed with the honor of giving its maiden speech.

With her Bachelor of Arts at Vassar College, Poughkeepsie, NY and took up another teaching job in Hollidaysburg, Pennsylvania with 5 hours dedicated teaching time and the rest to pursue her own private scientific investigations. She was given $150 of chemicals and equipment and keen to find out what she didn’t know. She had music lessons and committed the rest to analytics.

In 1871, Ladd Took up an increased teaching salary at Washington, Pennsylvania where she met and was enthralled by Washington and Jefferson College’s Professor of Mathematics and Engineering George B. Vose. Vose was a keen mathematical analyst and regular writer to The Mathematical Monthly under the leadership of MIT’s Professor John Runkle. Ladd started submitting both problems and solutions to London’s ‘Educational Times’ and ‘The Analyst: A Journal of Pure and Applied Mathematics’.

In 1872 she informally studied mathematics at Harvard and sat William E. Byerly and James Mills Pierce.

1876: Johns Hopkins University is the first research institution but was closed to women. It was a frequently debated topic amongst trustees and staff over when they would admit women into the institution until Martha Carey Thomas applied to study a classics degree. They were sufficiently convinced that having women at the institution it was officially decreed in 1877. Little did they know that Ladd had watched from the sidelines and waited for her moment which came when she applied directly to James Joseph Sylvester. Sylvester had first heard of Ladd through her publications to the Educational Times and it was him who urged the John Hopkins President Gilman that it would do wonders for the university to have a female mind like Christine Ladd’s there.

In 1878 Professor Gilman relented to allow Ladd to study mathematics unofficially and attend Sylvester’s lectures at the university. She later proved herself worthy through her work on the antilogism formula and “The Algebra of Logic” dissertation to the institution but still refused to grant her the fellowship title or her doctorate Ladd was worthy of. This was purely down to the fact that Ladd was a female and she had to wait until 1926 before the university awarded these to her.

In 1882 Christine married her Hungarian-born Mathematics Professor husband Fabian Franklin who had been her graduate examiner at Johns Hopkins. She turned her hand to psychological topics: perception and vision physiology. Her first psychology paper on improving the horopter definition. Five years later Ladd-Franklin as she was now known received Vassar’s only honorary degree.

Between 1891-2 Christine and Fabian travelled to Europe during Fabian’s sabbatical year and while there developed Ladd-Franklin theory of vision whilst studying in Germany at George Elias Muller’s laboratory. Her findings critiqued the leading views of the day by Hermann von Helmholtz and Ewald Hering but later brought her to prominence because it emphasized the evolutionary development of increased differentiation in color vision and assumed a photochemical model for the visual system.

In 1895 Christine and Fabian moved back to America when Fabian took up the editor position at ‘Baltimore News’. Christine served as a co-associate editor of ‘Dictionary of Philosophy and Psychology’ edited by Princeton’s J.Mark Baldwin as well as a co-collaborator on the dictionary’s logic entry. She published papers on mathematics and binocular vision: ‘The Algebra of Logic’ (1883); ‘The Nature of Colour Sensation’ (1925) and ‘Colour and Colour Theories’ (1929).

During 1904-1909 Ladd-Franklin returned to JHU to teach logic and philosophy in the Arts and Sciences department and only permitted to teach a single course per term. She was a philosophy lecturer on a yearly basis for 5 years.

In 1910 Fabian was appointed New York Evening Post’s Associate Editor and Christine taught a course per term without job title nor salary at Columbia. She remained there for the rest of her life until 1930.

By 1921 Ladd-Franklin was a New York Times correspondent where she used her platform to rebuke the all-male board at the American Academy of Arts and Letters highlighting the great work that American Psychological Association and American Philosophical Association’s President Mary Whiton Calkins of Wellesley had done. Ladd-Franklin hoped that the AAAL would start admitting and electing women to the board.

In 1924 Ladd-Franklin never relinquished her need to keep pushing for women’s rights and still advocated economic discussion groups for women because they had been given the vote.

She was still writing witty articles and wrote one in 1926 in response to a crime wave in New York City.

In 1929, Ladd-Franklin had her book ‘Colour and Colour Theories’ published. It was a 25 papers compilation of all the work on vision studies she researched and reported findings on. She shared this knowledge delivering her papers at international and American psychology conferences.

Christine died in 1930 aged 81 Fabian died aged 86 in January of 1939. They were survived by their daughter Margaret Ladd-Franklin who became a leading member of the women’s suffrage movement.

Born in 1853, Puerto Rico into a family of educators so inclusively imparting knowledge onto others was encouraged. She was nicknamed the “Flower of the Valley”.

Roqué’s mother was also a teacher taught her daughter to write by the age of 3 but she died soon after. Her father, grandmother and aunts continued to encourage Ana to learn.

In 1860 Roque Sent to boarding school by her father where she outpaced her classmates at twice the speed and graduated two years later. Roque dedicated her time and efforts to scientific studies in botany, zoology, astronomy, geology and meteorology.

Roqué started her career aged 11 when she was employed as a teacher’s assistant and by 13 had started a school of her own at her home. She wrote a geography textbook for her students later adopted by Department of Education of Puerto Rico.

By 1872 Roqué had married a wealthy land and slave owner Luis Duprey and she made it a point of her marriage that she would educate the slaves and not force them to bow to their masters. A year later Puerto Rico freed their slaves for good with the abolishment of slavery.

Roqué and Duprey had 5 children but only 3 made it to adulthood. By 1878 they moved the whole family to San Juan but the family’s happiness was short-lived when Duprey died leaving Roque to raise their children alone. Roque continued her teaching career in Arecibo which meant travelling 50 miles west of San Juan and where she earned her Philosophy and Science bachelor’s degree. Whilst her children were still young Roqué held her classes on the roof of her home teaching astronomy.

In 1893 she founded ‘La Mujer’ women-only magazine in Puerto Rico and contributed articles to El Mundo, El Buscapié and El Imparcial. She continued writing articles, scientific papers and published books: ‘Sara, La Obrera’ (The Female Worker); ‘Luz y Sombra’ (Light & Shadow). She also founded ‘La Evolución’, ‘La Mujer del Siguió XX’, ‘Álbum Puertorriqueño’ and ‘Heraldo de la Mujer’.

In 1898 America invaded Puerto Rico and a year later Roqué was appointed Normal School of San Juan’s director. Roque taught her students English to communicate with American officials. Keen to have generations of excellent teachers Roqué established a teaching academy, girl’s high school ‘Liceo Ponceño) and Mayagüez College later a part of the University of Puerto Rico in 1902.

Roqué authored the book that made her a household name. It was the most comprehensive study of flora covering 6000 species and their uses in the Caribbean called ‘Botany of the Antilles’ at the beginning of the 20th century. It was written for all mainstream audiences to use (farmers, doctors and parents) at the time it wasn’t published because it did not align with the thoughts of leading male botanists of the time.

A civil historic moment came when the Jones Act passed in federal government in 1917 allowing all male Puerto Ricans to vote spurring Roqué and those like her to change things so that women could be included. With those who were well connected they established ‘Liga Femínea Puertorriqueña’ (The Puerto Rican Feminine League) dedicated to fighting women’s suffrage. The platform that she had earned with her articles allowed her to advance the suffrage movement in Puerto Rico.

In 1921 the 19th Amendment didn’t apply to Puerto Rico so the LFP had a name change to Liga Social Sufragista (The Suffragist Social League) to help secure civil and political rights for all women to be able to work in public office and hold the highest position if they so wished.

In 1925 Roqué set up ‘Association of Women’s Suffragists’ only available to the most literate Puerto Rican women worried they might lose power if poorer, women of color got involved in the movement. As a result, Puerto Rican lawmakers approved of restricted suffrage in 1929 only out of fear that Congress might intervene and apply pressure.

In 1932 Roque received an honorary doctorate from the University of Puerto Rico and high schools in Humacao and another in Chicago were named after her.

In 1933 Roqué was the first female to enter the Puerto Rican Athenaeum dedicated to arts, music and literature. Roque died not long after and did not live to see universal suffrage passed for all adult women in 1935.

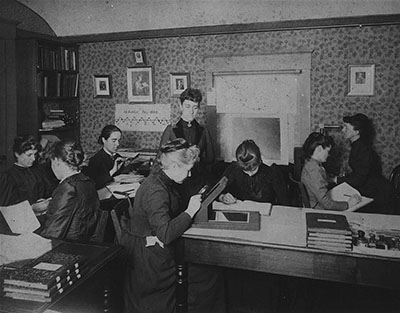

Born 15th May 1857, Dundee, United Kingdom was a Scottish-American astronomer. She was the first female manager to supervize 14 women, was one of the most noted and accomplished human female computers and created a classification system according to how much Hydrogen observed in stars’ spectra.

May 26th 1877 Williamina married James Orr Fleming. Fleming had been employed as a teacher before she took her family including her young child to Boston, Mass. James deserted his family so Fleming and her child lived as maids in Professor Edward Charles Pickering’s home. Pickering frustrated with his male assistants declared his maid would be better at the job so he hired her to do clerical work at Harvard College Observatory.

Fleming sailed her way through clerical work and started work on the star catalogue that later became the Henry Draper catalogue. In just shy of a decade, Fleming had catalogued over 10,000 stars, 59 gaseous nebulae, 10 novae and more than 310 variable stars.

In 1888 Fleming discovered ‘Horsehead Nebula’ providing vivid descriptions but barely cited in publications. William Henry Pickering took the photograph and theorized that it was dark obscuring matter. J.L.E. Dreyer, the compiler of the first Index Catalogue, omitted Fleming’s name from the list of discovered objects instead credited E. C. Pickering. In 1899 Fleming became Curator of Astronomical Photographs in honor of her achievements two decades after her initial work was published.

In 1906 Fleming was the first American woman to be elected Royal Astronomical Society of London honorary member and assigned title of Wellesley College’s honorary fellow.

In 1907 Fleming published 222 stars she had discovered without any of them attributed to her male colleagues. By 1908 Fleming was well-known enough to have her name attached to later discoveries including that of the first white dwarf star but not her earlier ones.

Like many of her predecessors Fleming also wrote her fair share of books: ‘Spectra and Photographic Magnitudes of Stars in Standard Regions’ (1911); ‘A Photographic Study of Variable Stars (1907).

Fleming was awarded Guadalupe Almedaro medal by Astronomical Society of Mexico for her star discoveries before she died in 1911.

Anna Winlock

Born in 1857, Cambridge, Massachusetts, America spent her career involved in producing astronomical data at Harvard.

Winlock’s father was the director of Harvard Observatory and Superintendent of Nautical Almanac. He died from a brief illness, left behind a widow and 5 children without financial support. She had worked alongside her father in the same way that Maria Mitchell had with William Mitchell her father and had become pivotal in her education. He had taken her on an expedition to see the sun’s eclipse at a makeshift camp in Kentucky where he also introduced his daughter to his cousins, sisters and aunts.

Harvard Observatory allowed Anna’s mother Mrs Winlock time to vacate the family home (owned by the Observatory) and helped find a new home in Cambridge. After the widow was settled in they cut off all financial support to the family. Thus 18 y/o Anna became the breadwinner.

Anna’s father’s death left Harvard Observatory with mountains of data to pile through and no system with which to file it in. Anna approached the Observatory to be employed in calculating and systemizing the data her father left behind. She found the 25 cent per hour an acceptable offer (now worth $5.98 in present money) and began working 6 days a week. Pickering needed new astronomers and employing women filled that gap. Known as part of Harvard Computers at the Observatory Winlock was supervised by Edward Charles Pickering.

It was the first time in astronomy that women were paid but shared the same salary as an unskilled worker: 25 to 30 cents an hour. It was much less than a man – a problem women still face today. The salaries he paid his woman employees was half that of normal calculation salaries of the time. Pickering said “To attain the greatest efficiency a skillful observer should never be obliged to spend time on what could be done equally well by an assistant at a much lower salary… [The Harvard] computers are largely women who can be got to work for next to nothing.”

Pickering was considered progressive and liberal of the period because of his willingness to invest in female employees. He was likened to a ‘true Victorian gentleman’ by one of his female employees. He worked closely with the financial benefactor Mrs Anna Palmer Draper who sponsored the Observatory’s activities and even encouraged an assistant to take a teaching position in mathematical astronomy at a Harvard-affiliated women’s school Radcliffe College.

It was not the norm to have women in the workplace nor in astronomy as they were expected to stay at home to take care of their families.

Winlock was one of the first 3 computers alongside Selina Bond, R.T. Rogers and Rhoda .G. Saunders hired in 1875. This paved the way for between 40 and 80 more women to join their ranks over the next 2 decades. Selina found herself in the same sticky predicament as Anna after a ‘rascally trustee’ squandered her father’s fortunes. Rhonda was a local high school graduate who came personally recommended by the Harvard President. R.T. Rogers and given her position was likely to have been a relative of an assistant astronomer like Anna was.

The consensus amongst medical experts was that that “a woman’s body could only handle a limited number of developmental tasks at one time – girls who spent too much energy developing their minds during puberty would end up with undeveloped or diseased reproductive systems.” They were made to work 6 days a week and given boring clerical jobs. There was no means of doing intellectually stimulating work unless they pushed their request at their own risk.

‘Observatory Pinafore’ is a musical parody and describes the conditions woman employees faced written from the point of view as an astronomer: struggling with their work, confronting astronomers with problems in environments that constrains their jobs or deny their role in scientific progress.

The Cambridge Observatory contributed to ‘Astronomischer Gesellschaft while the Harvard Observatory worked on the ‘Cambridge Zone’. William Rogers, the astronomer responsible for the ‘Cambridge Zone’ watched his collection of assistants come and while Winlock stuck it out earning Rogers’ respect as both assistant and scientific colleague. Whilst at the Observatory, she supervised the table listing of variable star positions in clusters and comparisons which was later published in Volume 38 of Observatory’s Annals.

Winlock worked to determined asteroid Eros’ path thought to be one of the largest inner asteroids. Found circular orbit for Ocilo asteroid and helped verify what elements it was made from. She carried out a significant independent investigation on North and South poles cataloguing all the stars was a complete compilation. This work was published in the Observatory’s Annals Vol.17 parts 9-10.

She died in 1904 in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Born in 1861 in Cavendish, Vermont but the family settled in Westford, Massachusetts.

Stevens’ father was a carpenter and handyman and owned enough property in Westford to pay for his children to attend school. Stevens was often at the top of her class.

In 1896 Stevens attended Leland Stanford University in California and in 1899 graduated with a Biology Bachelor’s Degree. At the turn of the 20th century Stevens earned her Biology Master’s Degree in where she undertook microscopic work and detailed records of marine life species. This work led her to her successful chromosomal investigations. She pursued a Biology doctorate at Bryn Mawr College, Philadelphia and there she met Thomas Hunt Morgan who became one of her professors. He was so impressed with her work she earned a fellowship to go and continue her studies abroad.

It was at the Zoological Institute in Wurzburg, Germany in Theodor Boveri’s laboratory where Stevens became interested in chromosomal behaviour because he was studying inherited chromosomes and their role in behavior.

In 1903 Stevens earned her PhD from Bryn Mawr and applied for research positions. Eventually she was employed by the Carnegie Institute because of how highly her professors Thomas Hunt Morgan, Edmund Wilson thought of her as well as the President of Bryn Mawr.

By 1905 Stevens investigated cytology & regenerative processes. In the Carnegie Institute Report contained Stevens work on sex determination in meal worms then later expanded and explored knowledge of other insects. Discovered ‘X’ and ‘Y’ chromosomes thereby establishing first firm link between an inherited character trait and/or behavior and a chromosome.

Her role at Bryn Mawr meant that Stevens had to teach but Stevens only wanted to be a researcher and wrote to Charles Davenport to work with him in his experimental biology lab. She died in 1912 of breast cancer before she could fill either role.

Born in 1862 in Vicenza, Austro-Hungarian Empire (Now Italy) where her father was a serving army officer. In 1871 Agnes’ father took retirement and his family back to his hometown of Brunswick, Germany. Agnes showed an early interest in science and had ambitions to study physics. She attended Municipal Girls’ School but found science wasn’t on the curriculum for her like it was for her younger brother Fritz who learned mathematics, chemistry and physics. With Fritz away from home Agnes borrowed his textbooks.

In 1883 Fritz, Agnes’ brother, attended a local technical university to gain a physics degree. He earned his PhD with Waldemar Voigt (invented term ‘tensor’) and revealed the Pockels electro-optic effect. He went to Heidelberg and became a Physics Professor. Agnes did not benefit from the same opportunities as her brother when it came to universities.

Whilst Fritz was away at university it was Agnes’ duty to care for her parents in Germany including doing chores but still continuing her studies by inheriting Fritz’ textbooks and Germany’s equivalent of the New Scientist ‘Naturwissentschaftliche Rundschau’. It was during these chores that she had a breakthrough the oils, soaps and household chemicals (what we would now call surfactants) on the surface tension of the water.

In 1891 Lord Rayleigh had an article published in ‘Nature’ which was reported on by ‘Rundschau’ and Pockels grabbed at the opportunity to furthering her education or if she was lucky enough to have him as her mentor by writing him a letter. Upon reception of her letter, Rayleigh forwarded it to Nature accompanying one of his own. This act of kindness from Rayleigh did little if at all to change Pockels situation who continued to care for her parents. During her spare time, she carried out further scientific investigations, published 2 further letters in Nature and several scientific papers in German journals with Fritz’ help. Together with Lord Rayleigh they designed and created a piece of equipment to help Pockels measure surface tension.

In 1917 Pockels got the breakthrough she had worked so hard for. Irving Langmuir, General Electric’s polymath head of research, used Pockels methods in his oil film studies which later helped him and Katherine Blodgett the first female scientist at GE invent Langmuir-Blodgett trough.

In 1931 Pockels was honored with the Colloid Society’s Laura Leonard award and an honorary doctorate from Braunschwieg University of Technology.

In 1932 Wilhelm Ostwald published Pockels memoir.

She died in 1935.

Annie Jump Cannon

Born December 11th 1863, Dover, Delaware and was the Eldest daughter of Wilson Cannon, a Delaware state senator, a suffragist and member of the National Women’s Party and became an Astronomer. She was profoundly deaf which some have attributed to her suffering from a bad cold when she was a child. To overcome this obstacle, she learned to lip-read.

Between 1877-84 Cannon attended Wellesley College & studied Physics and Astronomy then attended Radcliffe College between 1895-97 and returned to Wellesley College in 1907.

Cannon set to improving Fleming’s classification system by creating her own still used today: stars are divided into spectral classes (O, B, A, F, G, K and M) and they are determined by the Balmer absorption line strength associated with the temperature of Hydrogen. This improved classification system was adopted by the International Astronomical Union in 1922 as the official standard. In her entire career Cannon classified around 350,000 stars.

In 1931 Cannon secured her place in the history books as the first woman to be awarded the Henry Draper Gold Medal by the National Academy of Science.

In 1938 Harvard appointed Cannon as the William C. Bond Astronomer after Harvard College Observatory’s first Director and renamed Cannon’s classification system “Harvard System of Classification”.

She retired in 1940 but carried on contributing to her field in the Observatory until a few weeks before her death. Much like her predecessors, Cannon’s work was undermined and attributed to her male colleagues rather than herself.

She died 13th April 1941 in Cambridge, Massachusetts, America.

Henrietta Swan Leavitt

Born July 4th 1868 in Lancaster, Massachusetts and just like Cannon, Leavitt was also profoundly deaf and relied on her ability to lip-read to communicate.

Between 1886-88 Leavitt went to Oberlin College and transferred to the Society for the Collegiate Instruction of Women (later renamed as Radcliffe College) and graduated in 1892.

Leavitt first developed an interest in astronomy in her senior year in 1895 when volunteering as an assistant at Harvard Observatory. By 1902 Leavitt was employed in a full-time position. She joined Edward C. Pickering’s project and became an associate of Williamina Fleming and Annie Jump Cannon. Thanks to Fleming and Cannon’s success at the Observatory, Leavitt made the jump from clerical work to head of photographic stellar photometry department and made an impact with her astrophysical discoveries like her colleague Anna Winlock.

There, Leavitt observed some stars pulsating without influencing their overall brightness and discovered the Cepheid variable stars helped to explain universe’ expansion. She found brighter variables had longer periods which described the stars in question and the length of light pulsations and invariably led to the discovery of calculating distance across space. Edwin Hubble relied on Leavitt’s discovery to prove his theory that space continues beyond the Milky Way.

In 1907 Leavitt became involved in Pickering’s ambitious plan to determine photographically standardized values for stellar magnitudes. Photographic techniques were not affected by stars’ colors instead a standard magnitude to compare one with another. Leavitt focused on 46 stars within a radius of the celestial pole and formed new analysis methods which determined larger magnitudes than those within the same area. This moved the scale of standard brightness’ to 21st magnitude. Her work on this was subsequently published in 1912 and 1917.

Leavitt established secondary standard sequences using photos sent in from all over the world. Her North Polar Sequence was adopted by an international project ‘Astrographic Map of the Sky’ in 1913.

Pickering published her work, acknowledged her throughout but credited himself with Leavitt’s contributions. This was normal of the time for women to experience this from male colleagues and superiors which makes it more important to write about their achievements than see them wiped from the history books.

By her death in 1921, she had determined stars magnitudes in 108 areas of the sky. This method was used until improved tech improved photoelectrical measurements accuracy. This yielded a result of 4 novas and 2,400 variable stars which comprised of over half those known by 1930.

Born October 8th 1872 in Nashville, Tennessee and was an American pioneer, bacteriological chemist, food scientist & refrigeration engineer.

In 1892 Pennington studied chemistry and earned a proficiency certificate from University of Pennsylvania and graduated the University of Pennsylvania with a masters in 1895 when few women were able to go. In 1905 she earned her PhD and went to work at the US Department of Agriculture 1 year before the Pure Food and Drugs Act was passed which she played the majority part by leading pioneering research into safe and clean processing, storing and shipping foods of milk, poultry, eggs and fish. Amazing what can be achieved in a single year isn’t it?

She became the chief of the new Food Research Laboratory where she enjoyed a 4-decade career at USDA where she undertook research into harmful bacteria in milk. Her research led to first standards for milk safety and worldwide standards of food product refrigeration across the food industry and refrigerated rail carriages used to transport food. She quickly developed operational systems to scale, skin, quick freeze and dry pack fish fillets soon after the catch. Next she focused on studying refrigerated boxcar design efficiency on trains as she travelled across America establishing national ice-cold refrigerated train carriages including the best way to construct and insulate solving humidity issues during cold transport storage.

Pennington has 3 patents to her name including a poultry cooling rack, an egg treatment method that resisted bacteria and a container 100% sterile food products.

She was a consultant and VP at the American Institute of Refrigeration and awarded the Garvan-Olin Medal. In 2002 she was posthumously inducted into the Hall of Fame and in 2018 inducted into the National Inventors Hall of Fame.

She died on 27th December 1952.

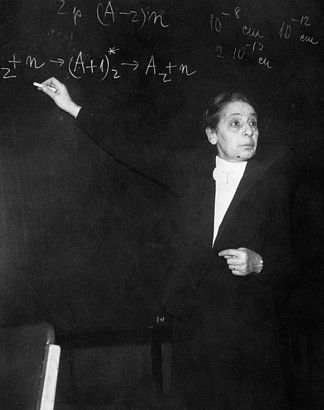

Lise Meitner

Born 7th November 1878 in Vienna, Austria and was a physicist and Nicknamed “Mother of Nuclear Power” despite playing no part in it. Very few are aware of the impact she has had on her chosen field.

She was the 3rd of 8 children in a Viennese Jewish family. Later 2 of her sisters converted to Catholicism and Lise herself became a Protestant. As the Nazis grew in power, the conversions were effectively redundant in targets on Jewish people.

1901: Lise attended the University of Vienna despite restrictions on female education. Ludwig Boltzmann was her professor and mentor where she realised where her passions truly lay. Her nephew, Otto Robert Frisch, later said that “Boltzmann gave her the vision of physics as a battle for ultimate truth…”

In 1906 Meitner earned a doctorate degree in physics at University of Vienna then a year later went to Berlin to continue her studies with Max Planck where she met the chemist Otto Hahn. She teamed up with Hahn and jointly discovered nuclear fission while competing against European competitors of Irene Curie, Frederic Joliot etc. Hahn and Meitner worked together for 3 decades both responsible for leading areas at Berlin’s Kasier Wilhelm Institute for Chemistry.

In 1934 Meitner, Hahn and Fritz Strassmann collaborated with Enrico Fermi who had produced radioactive isotopes and was looking for transuranic elements to solve his problem. By 1938 the problem had still not been solved.

Then came a truly pivotal moment in Meitner’s life with the German annexation of Austria, known as ‘Anschluss’. Given her Jewish family background and in spite of her conversion to Protestantism, she remained unsafe and was forced into exile for her own safety first to Stockholm and the Manne Siegbahn Institute as Sweden was one of few nations to remain neutral during both wars. Meitner, Hahn and Straussman continued their transuranic quest posed by Fermi. Hahn and Straussman were completely unaware of what Meitner had done but on November 13th 1938 Meitner met Hahn in Copenhagen in secrecy and together experimented on a uranium product they thought was radium but was in fact barium.

On January 6th 1939: Naturwissenschaften published the results of the experiment.

11th Feb 1939: Meitner and Frisch with the help of Bohr’s “liquid drop” model talked about their nuclear fission experiment in ‘Nature’.

In 1945 Hahn took the credit for the discovery and was duly awarded a Nobel Prize but Meitner went unrecognized because the Nobel committee failed to understand why Meitner had fled Germany and into exile. Hahn attempted to logically argue why this had happened whilst others made no mention of her. The committee’s mistake was never fully rectified until 1966 when the US Fermi Prize was awarded to all 3 contributors.

She died on October 27th 1968.

Born 1878, Oakland, CA, America and became an American psychologist and Industrial Engineer.

As the oldest of 9 children shy and home-schooled by her parents until the age of 9. Despite her deep introverted nature Gilbreth had a successful academic career despite her parents thoughts that she would never attend college.

Gilbreth undertook a Literature degree to prepare herself for a teaching career and graduated with honors in 1900. She was the University of California, Berkley’s first female commencement speaker and enrolled to study Masters in English Literature in 1902. She earned her PhD in English Literature and minored in Psychology at Berkley then completed her Psychology PhD at Brown’s University.

In 1921 Gilbreth was the first female member of the Society of Industrial Engineers’.

As an efficiency and organizational psychology expert, Gilbreth applied her findings not only in her job as management consultant for major corporations but to her household of 12 children and wrote a book on it called ‘Cheaper by the Dozen’.

Her husband Frank Gilbreth died suddenly of a heart attack in 1924 aged 56. Lillian continued to provide for her 12 children through management consultancy role and held management consultancy workshops at her home enabling her to continue her career and raise her children. Workshops grew successful in conjunction with Lillian’s growing reputation and taught courses at university and colleges (Bryn Mawr College, Rutgers University & Purdue University).

Gilbreth also achieved historic firsts as Purdue’s first female engineering professor at until her retirement in 1948 and the first woman elected to National Academy of Engineering in 1965.

During the Great Depression, Lillian was asked by President Hoover to join Emergency Committee for Unemployment. As a result Lillian set up a nationwide program called ‘Share the Work’ to provide relief for the stressful unemployment situation across America.

During the entirety of her career Gilbreth was awarded 20 honorary degrees, a member of the Society of Mechanical Engineers and a fellow of the Psychological Association. In 1944 Frank and Lillian were jointly awarded the Gantt Gold Medal from American Society of Mechanical Engineers and American Management Association.

In 1952 J.W.McKinney declared Lillian Gilbreth “The World’s Greatest Woman Engineer” because of her impact on management, innovations in industrial design, methodological contributions to time and motion studies, humanization of management principles and her role in integrating the principles of science and management.

In 1966 Gilbreth was the first woman to receive the Hoover medal for distinguished public service by an engineer. She remained prominent in the field of psychology and management until aged 90.

Gilbreth died aged 93 on January 2nd 1972 in Phoenix, Arizona.

Born February 10th 1883 in Howard County, Maryland and 1 of 8 children but orphaned aged 12 she was sent to boarding school for her education where it was still rare at the time for women to obtain a college degree.

In 1908 Graduated from Vassar College at Yale which the inheritance she had from her parents paid for. She kept her independence by filling teaching posts in San Francisco and Wisconsin before she was employed at AT&T as a manager of female computers.

In 1919 Clarke was the first woman to graduate with an electrical engineering Masters doctorate from Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). Even so there was difficulty in getting a job because there weren’t companies who hired female engineers. Clarke departed for Turkey heading for its capital to be the physics teacher at Istanbul’s Women’s College but didn’t stay there long because she still yearned to be a fully fledged engineer.

In 1922 Clarke was the first professional Electrical engineer in America employed by General Electric and issued a patent for a graphical calculator necessary to solve problems with electric power line over 250 metres transmission.

She was the first female as a Fellow, the first woman to present a technical paper from the Predecessor’s Society to the Institute of Electrical and Electronic Engineers. She actively encouraged women to get into STEM with a particular focus on engineering.

Clarke saved her best card until last when her critics never expected to hear of her role in bringing to the world transcontinental telephone communication.

In 2015 Clarke was posthumously inducted into the National Inventors Hall of Fame celebrates Inventors and Patent Holders.

One month before she was born on January 10th 1898, her father George R. Blodgett, General Electric's most infamous patent attorney was shot by a burglar evading capture before he hung himself for reasons that are still a mystery.

Katherine and her mother moved to France shortly after. Later Katherine moved back to NYC and attended Rayson School. She was top of the class in mathematics and physics.

In 1913 won a scholarship to Bryn Mawr College, Pennsylvania and in 1917 graduated with a bachelor’s degree in Physics from Bryn Mawr College. She was taught by her mathematics professor Charlotte Scott and physics professor James Barnes. She went to General Electric and met Irving Langmuir who had been Blodgett’s father’s colleague. Langmuir hired Blodgett after being impressed with her tenacity and she became his assistant and the first woman to ever do so. He was instrumental in continuing her education before thinking about applying for a role at GE. She graduated with a master’s degree in Chemistry from University of Chicago where she worked with Harvey B. Lemon on coal gas absorption properties and wrote a paper on gas mask materials saving millions of lives during the Second World War. This work was published after the Great War.

In 1924 she worked at Sir Ernest Rutherford’s Cavendish Laboratory the finest scientific institution in the world where she studied electron behavior in ionized mercury vapor.

In 1926 Blodgett was the first woman to earn a Physics doctorate from Cambridge University, UK. She returned home to America and GE to continue working alongside her mentor Langmuir focusing on thin films becoming a respected expert in her field.

In 1933 Blodgett discovered the color gauge. In 1938 surface chemistry and engineering expert Blodgett created non-reflecting glass securing 6 patents for her work and is often known as the Langmuir-Blodgett technology. The first to make glass appear invisible and have been applied in car windshields, store windows, cameras, showcases, spectacles, telescopes, picture frames and submarines.

During both wars she improved smoke screen technology and de-icing planes for military application and developed a device measured humidity and meteorological sciences.

Blodgett was subsequently honored from 1939-44 with honorary science doctorates from Elmira College, Brown University and Western College and Russell Sage College.

In 1951 Blodgett was awarded American Chemical Society’s Garvan Medal to the first industrial scientist and then by her hometown of Schenectady created the Katherine Blodgett Day for her contributions to science and civil causes. She was also American Physical Society and Optical Society member.

In 1963 Blodgett took retirement from General Electric and took up hobbies. She was an actress in her own theatre group in her town and volunteered time to civic and charitable causes.

In 1972 Won Medal from the Photographic Society of America’s Progress.

She died at home aged 81 in 1979.

Born in 1897 in Easton, Pennsylvania and grew up to be a Biochemist who developed the standard for TB testing by purifying a protein.

She had a lifelong limp after contracting polio as a child but Seibert never let this hold her back and earned herself a scholarship to Goucher College, Maryland. In the year the Great War of 1918 ended Seibert graduated Goucher College and got a chemist job at a paper mill. In 1923 she earned her Biochemistry Doctorate from Yale University focused on improved intravenous equipment safety creating saline solution that didn’t have any contaminants. In 1924 Seibert continued her post doctorate studies at the University of Chicago where she worked her way up first as an instructor then as an assistant professor at Sprague Memorial Institute, Chicago.

Seibert’s teaching career spanned across numerous colleges including 27 years at the University of Pennsylvania. By 1932 she had the title of full professorship at the University of Pennsylvania until her retirement in 1958.

It was during this period that Seibert made her biggest impact with her research into tuberculosis. Robert Koch had discovered in 1891 that animals who had experienced fragments of tb bacteria called tuberculin or alternatively dead bacteria injected into the skin experienced welts. This is known as the tuberculin reaction due to delayed hypersensitivity, an immune response from those who have had TB infections in the past or currently have it. Thus, physicians have the ability to diagnose those who have the conditions. At the time Koch had not started to create consistent batches of the active protein part of tuberculin. This didn’t give a uniform range of responses. Seibert’s purification process ensured that every reaction was the same across the board. In 1934 Seibert wrote about the discovery she called Purified Protein Derivative (PPD).

Her work had made breakthroughs saving lives just as it still is today. In 1938 The National Tuberculosis Association awarded Seibert the Trudeau Medal. By 1940 it became the global standard in tuberculin tests after she made drastic improvements to the test with the use of the PPD which took centre stage in mainstream public health in creating the vaccine. In celebration of what her work had done in society in 1941 the American Chemical Society awarded her the Garvan Medal.

Seibert left the University of Pennsylvania and went to St. Petersburg, Florida to be the Cancer Research Laboratory Director. She started writing her autobiography and continued to write up findings in scientific research papers “Pebbles on the Hill of a Scientist and published in 1968.

In 1977 Seibert’s health took a downward turn and Seibert took a step back from her work after publishing numerous of scientific research papers.

1990: Inducted into the National Women’s Hall of Fame.

She died in 1991.

Conclusion

We have a lot to thank these women who wrote themselves into the history books with their years of firsts. Every woman here has a legacy that can be seen everywhere you look in today’s world. Ok so their achievements aren’t shouted from the rooftops as much as their achievements deserve they really deserve. From the sky, to the food we put in our bodies, to our own health as women in the realm of gynecology and especially vaccines.

If you think these women were incredible you’re really going to enjoy meeting the 20th and 21st century legends in our second part.

What we at VUSE really want to know is…will you be the next to join their ranks?

If you don’t know we’re hiring and we would love to have you on board, you can see all of our vacancies here.