Welcome back to Part 2 of our HERstory of Women in Tech (read part 1 here) as we celebrate the end of Women in History month! We hope you’ve enjoyed meeting some of the incredible women who’ve made their mark on the world, in science and as everyday women. This time we’ll be introducing you to the extraordinary 20th and 21st century women who have helped breakdown barriers, encourage more women into STEM and created history of their own.

20th Century

The 20th century brought the industrial revolution, collapse of global empires, two world wars and a 180-gender swap in attitudes towards STEM in the latter stages of the 20th century. Despite both wars bringing a lot of misery and lost loved ones, it also encouraged women to return to the workplace taking over the men’s STEM jobs. Women picked up engineering skills with large factory machinery and were telephone operators. 80% of telephone operators in 1900 were women and continued to be operators until the 1960s.

Dr. Cecilia Payne-Gaposchkin

Born 1900 to a London barrister, historian and successful musician father and Prussian mother. She was 1 of 3 children (her brother was an archaeologist and her sister was an architect) and were raised by their widow mother after their father drowned in a canal when then Cecilia Payne was just 4 years old. Cecilia was not short on remarkable family members to follow in the footsteps of with historian uncle Georg Heinrich Pertz and Swedenborgian writer uncle James John Garth Wilkinson.

Payne went to St Paul’s Girls’ School then in 1919 earned a scholarship to complete schooling at Newnham College, Cambridge University to study botany, physics and chemistry even though women were not granted degrees until 1948. Astronomy became another interest when she attended an Arthur Eddington lecture. Eddington described his studying and research trip to Principe, Gulf of Guinea off Africa’s west coast with the intention of proving or disproving Einstein’s theory of relativity by photographing stars closest to a solar eclipse.

Teaching was the only career option available to Payne in the UK so she looked for a grant to help her travel to America. The Director of Harvard College Observatory, Harlow Shapley, had just launched an astronomy graduate program granting women fellowships to study at the observatory. As the second woman to ever be granted a fellowship by the Observatory, Payne finally had her ticket to America, so she packed her bags and left in 1923.

Whilst at Harvard, Shapley motivated Payne to write a PhD thesis which she called “Stellar Atmospheres, A Contribution to the Observational Study of High temperature in the Reversing Layers of Stars”. It was so well received that she was the first person to earn an astronomy doctorate from Radcliffe College (now a part of Harvard). At first she faced opposition from fellow astronomer Henry Norris Russell of Princeton University, New Jersey who went to great lengths to prevent Payne from presenting her conclusion that the Sun was made from different elements to Earth because it disagreed with the then-current opinions. After undertaking his own experiment, he came to the same conclusion as Payne and published his findings. With a brief acknowledgement of Payne in his write-up, it was Russell who was awarded recognition in relation to the discovery despite Payne’s work.

Payne continued studying stars in a bid to work out the Milky Way. With her assistants help, Payne made 1.25m observations and a further 2m when studying variable stars and Magellanic Clouds to understand stellar evolution. In collaboration with her husband Sergei Gaposchkin, Payne had her second book “Stars of High Luminosity” published in 1930.

Payne-Gaposchkin spent her entire career at Harvard despite arriving on a fellowship without an official job title. She was only seen as Shapley’s technical assistant for 11 years between 1927-38. She debated whether to leave Harvard due to lack of job and salary prospects. Shapley, on hearing that Payne-Gaposchkin was despondent about her situation gave her the “Astronomer” title which she had later changed to “Phillips Astronomer”. In 1943, Payne-Gaposchkin was elected to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences as a Fellow. until 1945 there wasn’t a record of any of the classes she had taught. Amongst her pupils were: Helen Sawyer Hogg, Joseph Ashbrook, Frank Drake, Paul W. Hodge and supervised a leading LGBT+ rights activist Frank Kameny who was dismissed from his job at the time because it was illegal to be gay.

In 1954, there was a change of Harvard College Observatory Director when Donald Menzel was brought in. He made Payne-Gaposchkin Harvard’s Faculty of Arts and Sciences’ full professor two years later. She was also the first woman to be elected Chair of the Department of Astronomy.

In 1966 Payne-Gaposchkin hung up her teaching boots and was named Harvard’s Emeritus Professor. She chose to spend the rest of her career as she had begun it in research. She was a Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory staff member and for two decades was the Harvard Observatory’s journal and book editor.

Payne-Gaposchkin’s impact at the Harvard Observatory wasn’t just felt amongst her students. Her employment along with all the women who had come before her convinced the Harvard Observatory it’s investment in female STEM careers was a win-win for all involved. Harvard Observatory was renowned amongst the scientific community for giving women more opportunities there than anywhere else in America.

We have Payne-Gaposchkin to thank for inspiring Richard Feynman and his sister Joan into astrophysics, who saw CPG’s work in a textbook and wanted to chase the same dream despite initial skepticism from their mother and grandmother.

Payne-Gaposchkin privately published her autobiography “The Dyer’s Hand” (later published for public consumption entitled “Cecilia Payne Gaposchkin”) and died in 1979.

Dr. Grete Hermann

Born March 2nd 1901 in Bremen, Germany was a Physicist, Mathematician, Philosopher researcher and teacher.

Hermann was the 3rd of 7 children in a middle-class Protestant family. She came from a long line of deep religiously acquainted people with pastor grandfathers, merchant and latterly street preacher father and an active church-going mother. She was enrolled at the New School in Bremen but was not religious herself.

By the time she left school in 1921, Hermann had become a qualified teacher for German secondary schools. At Göttingen University and Freiberg University Hermann studied mathematics and philosophy. Mentored at Göttingen by Emmy Noether, Hermann undertook her PhD in mathematics studies and wrote thesis ‘The Question of Finitely Many Steps in Polynominal Ideal Theory’ in 1926. She established algorithms for abstract algebra and established foundations for modern computer algebra. Keen to follow Noether into the field of physics and mathematics. Her first teaching gig was at the Walkenmühle School then as Professor at Bremen’s Pedagogical Institute.

While at Göttingen she also became interested in socialism and philosophy from working alongside leading philosopher Leonard Nelson between 1926-27. She joined his socialist youth group Internationalen Sozialistischen Kampfbund (ISK) supported by big scientific names Albert Einstein and Kathy Kollwitz who fought against social injustice and capitalism. She carried on his cause after Nelson died in 1927 and joined Nelson’s other group “Internationalen Jugend Bund”. During the Nazis’ rise, ISK was not only the most active opponents then and during the Second World War but also joined other opposition groups to wrestle their beloved Germany from the dictatorship. Hermann fought its cause through teaching resistance members and as “Der Funke” editor. She worked on a course of education and ethical philosophy published in 1932.

As a physicist she was famed for her work on uncovering an error in John von Neumann’s logical quantum theory interpretation that it was not feasible to have hidden variables in quantum mechanics. This work was ignored for more than 3 decades despite the Academy of Sciences of Saxony presenting Hermann the Richard Avenarius Prize.

Like many of her scientific compatriots, Hermann was forced into exile with the school first to Denmark then onto Paris when Germany occupied Denmark and ended up in the UK. It was there she met Eduard Henry and entered a marriage of convenience to acquire British citizenship for her own safety. This was the only period of her life she wasn’t living in Germany.

Hermann divorced Henry and spent the post-war years in her hometown focused on political and philosophical causes than on STEM subjects particularly after Emmy Noether’s death. She had fallen out of love with STEM because the war prevented her from carrying out much of the research she was interested in.

She died April 15th 1984 in her hometown of Bremen, Germany.

Dr. Barbara McClintock

Born June 16 1902 in Hartford, Connecticut was an American geneticist and world-renowned cytogeneticist. She was the eldest of four children and aged 6 the McClintocks moved to Brooklyn. In 1919, McClintock graduated Erasmus Hall High School and then attended Cornell University to study her Bachelor, Masters and PhD in botany finishing in 1927. At the time women were prevented from studying genetics at Cornell, McClintock was part of a group that studied plant genetics in maize cell structure.

In the 1930s the National Research Council, Guggenheim Foundation and other organizations gave McClintock the funding she needed to pursue cytogenetics at the University of Missouri, California Institute of Technology and Cornell. She also spent six months in Germany during 1933-4 but with the growing rise of Nazism she had her trip cut shorter than anticipated.

McClintock returned home to Cornell then moved to the University of Missouri in 1936 to work with the geneticist powerhouse Lewis Stadler. She left the position in 1940 when she realized there was no job progression and moved to Cold Spring Harbor, Long Island to work at Carnegie Institution of Washington’s Genetics Department. She remained there until retirement in 1967 when they conferred the Distinguished Service Award on her. During that time, she traveled collecting maize samples in South and Central America for 20 years and mentored students. They invited her to stay on at the Laboratory as a research scientist until she died in 1992.

In 1944, the National Academy of Sciences elected her to be their 3rd woman and a year later was the Genetics Society of America’s first female elected president. She was the first woman to be awarded the National Medal of Science by President Richard M. Nixon.

In 1981, McClintock and her team collated all the data recorded over the 20 years of field trips and published the findings in a book called “The Chromosomal Constitution of Races of Maize”. She was the MacArthur Foundation Grant’s first recipient (nicknamed the Genius Grant) and given the Albert and Mary Lasker Award in the same year.

In 1983, McClintock first woman to be awarded an unshared Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for her “jumping gene” discovery. Her research demonstrated the existence of “mobile genetic elements,” also known as genetic transposition which is the capacity of genes to change position on a chromosome.

She died in 1992. Today her work still influences the world’s community of geneticists.

Admiral Dr Grace Murray Hopper

Born in 1906, NYC, Hopper was an American computer scientist and United States Navy Rear Admiral. She attended Yale University in 1930 earning her mathematics PhD and in 1943 joined the Naval Reserve.

In 1945, with a decade of teaching under her belt, Hopper, 15 pounds below the 120 lbs minimum requirement and needing special exemption, signed up to the Navy’s volunteer branch. She joined the Naval Reserve’s Eckert-Mauchly Computer Corp in 1949 and designed a compiler that translated programming instructions into computer codes. It was Hopper who came up with the term computer bug after finding a moth inside the machine.

In 1957, her division created and developed FLOW-MATIC, the first accessible English language computer program. She was told that it wouldn’t work because computers wouldn’t be able to understand English. Hopper was famed for saying “Humans are allergic to change. They love to say, ‘We’ve always done it this way.’ I try to fight that. That’s why I have a clock on my wall that runs counter-clockwise.” At first Common Business Orientated Language was the Navy Standard then became the world’s most widely used business coding language.

Aged 79, Hopper was America’s oldest Rear Admiral naval officer before retiring in 1986. After retirement from Naval Reserve, she set about standardizing the navy’s computer languages. She was given numerous awards in recognition for the work she did.

Admiral Dr. Hopper died in 1992 and was posthumously awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 2016 by then-sitting President Barack Obama.

Rachel L. Carson

Born May 27th 1907 in Springdale, Pennsylvania was a Marine biologist and environmental campaigner. She experienced a simple childhood and together with her inherited love of nature from her mother inspired her to write about them before she went to university to study marine biology.

In 1929, Carson graduated from Pennsylvania College for Women later renamed Chatham University with her marine biology bachelor’s degree. During the Depression era, the US Bureau of Fisheries employed her to write radio scripts and wrote feature articles for the Baltimore Sun. In 1932 she graduated with a Masters in Zoology from John Hopkins University & studied at the Woods Hole Marine Biological Laboratory.

In 1936, Carson was employed as a scientist and editor for 15 years in the Federal Service then promoted to US Fish and Wildlife Service. As their Editor-in-Chief she wrote pamphlets on conservation and natural resources as well as editing scientific articles.

In 1937, Carson wrote ‘Undersea’ in lyric prose in which she compiled her government research and had published with Atlantic Monthly. In 1941 she compiled ‘Under the Sea-Wind’ containing all the ‘Undersea’ articles she had ever written and published at the Atlantic Monthly.

After the Second World War, Carson grew concerned about using synthetic chemical pesticides and set about educating the public on their long-term effects due to misuse. The chemistry industry and government alike were outraged by Carson’s comments calling her an alarmist. Carson bravely reminded the public that as a species we are at just as much grave risk as the ecosystem which sustains us.

In 1952, she wrote and published her prize-winning ocean study ‘The Sea Around Us’. Her resignation from her role in government service came not long after stating that she wanted to continue her writing career.

In 1955, Carson marked the beginning of her writing career with ‘The Edge of the Sea’. These ocean biographies synonymous and inextricably linked to Carson, brought her to a level of fame and notoriety on par with Sir David Attenborough both as a naturalist and science writer to her public audience.

In 1956, Carson wrote and published ‘Help Your Child to Wonder’ educating the public on Earth’s wonders and beauty and in 1957 wrote the follow up ‘Our Ever-Changing Shore’. She planned another book on ecology of life exploring how human beings had the power to make changes for the better but are to blame for causing irreversible damage. Her attitude was it wasn’t too late to make changes but her pleas fell on deaf ears. Here we still are, the same messages pumped out to us nearly 70 years later and climate change still poses an ever-increasing threat to all lives on Earth just as Carson had warned us.

In 1962 Carson had “Silent Spring” published. This book is often referred to as the origins of modern environmental movement. In it she argued against then-current agricultural scientists and government practices calling for a complete overhaul in the way people saw the natural world. A year later she testified before Congress calling for change in agricultural policies to protect both human and environmental health.

Carson died after a long battle with breast cancer in 1964.

Mary G. Ross

Born August 9th 1908 in Park Hill, Oklahoma.

As a child Ross went to live with her grandparents in Tahlequah, Cherokee Nation to attend the school her twice-times great grandfather Cherokee Chief John Ross built on Cherokee Female Seminary grounds.

In 1924, Ross graduated with a Mathematics Bachelor’s Degree from Northeastern State Teacher’s College. She returned to Oklahoma to teach mathematics and science then moved to Washington DC to work in the Department of the Interior building for the Bureau of Indian Affairs. A year later she was reassigned to the Santa Fe Indian School, New Mexico as an advisor to the female students. In 1938, Ross had completed her Mathematics Master’s degree from Colorado State Teachers College after taking only summer classes. Ross was enthralled by the night’s sky and she took every available astronomy class to learn more about the stars.

Then came the Second World War and the jobs previously dominated by white men were handed out to women while they were away at war. Ross’ role was to design fighter jets and large planes from 1942. When the war was over and the men returned home, Ross carried on working for Lockheed in California as her fellow women were forced out and back home to take care of the family. She was sent to University of California, LA to become the first fully qualified Native American engineer.

Ross co-founded the Advanced Development Program known by its familiar name the Skunk Works in 1952. It was a project shrouded in secrecy which is why much of what Ross and her 39 co-founders achieved remains unknown to the public. The parts of it that have been revealed focused on designs for interplanetary space flights, in-crew space flights, missiles and Earth-orbiting satellites. Ross detailed how likely a space flight to Mars and Venus both uninhabited and inhospitable to human life might work in the future.

Ross took retirement in 1973 and focused her efforts on encouraging more Native Americans into STEM and in 2004 took part in Washington DC’s National Museum of the American Indian’s opening ceremony.

She died April 29th 2008 aged 99.

Dr. Virginia Apgar

Born June 7th 1909 in Westfield, New Jersey was a American Physician, anesthesiologist and medical researcher. She was the youngest of 3 children and a keen violin player. Like a lot of her 19th century female predecessors, Dr Apgar was introduced and inspired by her amateur inventor and astronomer father who was heavily interested in the sciences.

By high school age Apgar was determined to pursue a medical career. Though she was an excellent student of the sciences she was so bad in-home economics that she never learned to cook. In 1925, Apgar secured a place at Mount Holyoke College majoring in zoology and paid her way through her studies via part-time jobs. Her college trademark was as a fast talker and with boundless energy undertaking numerous extracurricular activities (7 sports teams, reported for college newspaper, actor in dramatic productions and played violin in the orchestra).

In 1929 Apgar graduated from Mount Holyoke College with a Bachelor of Arts and began medical training at Columbia’s University College of Physicians and Surgeons. She was 1 of 9 female students in a 90-student class but was not put off by this.

In 1933 Apgar earned her Doctorate in Medicine and undertook Surgical Internship at Presbyterian Hospital, NYC for 2 years. Her mentor Allen Whipple concerned about economic prospects of female surgeons post-Depression era suggested a transfer to anesthesiology as this was viewed as a medical practice instead of nursing.

She trained for 1 year on the Presbyterian’s nurse-anesthesiologist course followed by residency programs led by Ralph Waters and Emery Rovenstine at respective University of Wisconsin and later at New York’s Bellevue Hospital.

In 1938 Apgar returned to Presbyterian Hospital and became the first woman to ever have the Director of Anesthesia post in the Surgery Department. Her responsibilities included recruiting and training of anesthesiologist residents, teaching medical students on rotation, coordinating work and research.Apgar’s redevelopment of the anesthesia team brought in an influx of more physicians than nursing staff establishing an education program for those who wanted to work in the profession. As such she became a much loved and respected teacher.

In 1949, the Anesthesiology Division became a department and after all of Apgar’s influence in its running fully expected to be named Chair. The role was given to a male colleague Emanuel Papper and Apgar was the first woman to hold a full professor of the department at the hospital. Relinquished of admin tasks, Apgar focused on teaching and researching anesthesia obstetrics with particular focus on newborns affected by maternal anesthesia and increasing neo-natal survival rates. Since the turn of the century infant mortality had decreased but neo-natal deaths remained high. Over the course of the next decade in the musical side to her life, a close friend introduced Apgar to instrument making where they create and build together two violins, a viola and a cello.

In 1952 she developed the Apgar Score alongside colleagues L. Stanley James and Duncan Holaday ranking a baby’s well-being after birth from measuring heart-rate, respiration, movement, irritability and body color post-birth to determine if immediate medical intervention needed. Their contributions to neo-nation blood chemistry helped to support the Apgar Score test and is now a standard worldwide procedure on all babies. Apgar had shared a part of 17,000 births by the late 1950s and in shaping the Apgar Score was able to diagnose birth defects comparing results with others and where they sat in score results.

In 1958, Apgar went on sabbatical leave and went to Johns Hopkins School of Public Health where she took up a place on its Master of Public Health Program to become better at statistical analysis in her work at Columbia and pursued her interest in birth defects prevention and diagnostic improvements.

In 1959, the National Foundation-March of Dimes appointed Apgar to lead it’s Congenital Malformations Division. She started her new role that June using her trademark and people skills she travelled all over America every single year giving talks to all audiences about the urgent need to detect the early signs of birth defects as well as further commitment to research. The impact Apgar had in the role doubled the NF’s income while she was there sealing her place as a much-valued ambassador of its work.

Apgar was not short of amassing honors. In 1964 she was awarded an honorary doctorate from the Woman’s Medical College of Pennsylvania. In 1965 she was awarded an honorary doctorate from Mount Holyoke College. Between 1965-71 Apgar was employed as a lecturer at Cornell University’s School of Medicine. In 1966 Apgar was conferred the American Medical Women’s Association’ Elizabeth Blackwell Award & American Society of Anesthesiologists’ Distinguished Achievement.

During 1967-8 Apgar was promoted to Director of Basic Medical Research at the NF. Then in 1971-4 was Vice-President of Medical Affairs and Cornell University School of Medicine’s Clinical Professor teaching teratology becoming the first to ever hold such a position in pediatrics.

In 1972 Apgar co-authored ‘Is My Baby All Right?’ with Joan Beck which combined child and family welfare as well as teaching talent.In 1973 Johns Hopkins School of Public Health appointed her Medical Genetics lecturer.

Her career occupied much of her time but Apgar carried on her extra-curricular activities she had participated in throughout her academic career making sure that her violin was always with her so she could play with amateur chamber quartets whenever she could. She loved gardening, fly-fishing, golfing and stamp collecting. In her fifties, driven by the quest to fly under New York’s George Washington Bridge.

She was bestowed: Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons’ Alumni Gold Medal for Distinguished Achievement, American Society of Anesthesiologists’ Ralph M. Waters Award & Ladies Home Journal’s Woman of the Year.

Apgar had long career that didn’t end in retirement nor included marriage nor children and wrote more than 60 scientific articles, short newspaper and magazines essays.

Publicly, Apgar avoided women’s organizations and causes declaring that females are not limited in a scientific career due to gender. Privately, she did air concerns about gender inequalities around the subject of salaries but found other means of success in creating new scientific areas.

In her final years, she was forced to slow down due to progressive liver disease and died on August 7th 1974 at Columbia-Presbyterian Medical Center where she had spent much of her life.

Twenty years later, Apgar’s memory and life was honoured with her face on a postage stamp and a year later was Posthumously inducted into the National Women’s Hall of Fame in 1995.

Klára Dán von Neumann

Born 1911 in Budapest, Hungary to a wealthy Jewish family and grew up during the First World War when Hungary was part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. She was sent to an English boarding school only to become Hungary’s national figure skating champion. Her adolescence had the greatest minds, artists and scientists of the day throughout the 1920s.

By the time she was 25 years old, Klara (known affectionately as Klari) had married, divorced and remarried. She fell in love with a married Hungarian mathematician John von Neumann whose wife ran off with J.B. Horner Kuper and later became Long Island’s Brookhaven National Laboratory’s first employees. John and his first wife were soon divorced then he and Klara married.

Klara followed John to Princeton as the Nazi’s attempted to swallow up as much of Europe as they could and with algebra and trigonometry knowledge at high-school level but the same numerical interests as her husband, the Office of Population Research at Princeton employed her to explore population trends.

John moved out to Los Alamos, New Mexico to work on the multitudes of calculations as part of the Manhattan Project and Klara remained in her full-time position at Princeton. Scarred from the outcome of his work, John got involved in making improvements to weather forecasting using the ENIAC. He contacted meteorologists across the world including America and Norway. Klara who was now proficient in mathematics went to visit him in Los Alamos. She helped him translate equations into numbers and mechanical instructions into the machine without built in memory or an operating system. Despite the difficulty (at least by today’s standards) Klara said it was “very amusing and rather intricate jigsaw puzzle.”

John and Klara led an initiative on the ENIAC and had it moved to Maryland (scroll down to read more in detail). Klara trained 5 of John’s colleagues to be an ENIAC programmer and worked 32 consecutive days on the machine creating a new control system, coding as well as taking it in turns to run the machine. By the end, Klara had to be admitted for a check-up to Princeton because she had lost 15lbs and completely exhausted.

In 1950, the ENIAC had a group of meteorologists onboard and the latest updates had been in place for a whole year making it easier for them to do their job. Klara was part of a team setting up the machine to produce 2 12-hour and 4 24-hour retrospective weather forecasts. Klara verified the code for such a monumental physics experiment. The meteorologists acknowledged Klara as one of the Meteorological Project’s leaders training scientists to program the computer despite not contributing any herself. She also kept a close eye on the 100,000 punch cards it took to tell the machine what to do as the human form of it’s memory storage as well as hand-punching the cards into the machine herself.

By 1956, John was wheelchair bound and died from cancer the following year which was thought to be the result of his contact with radiation during the Manhattan Project days. In John’s posthumous book “The Computer and the Brain” Klara wrote the preface and later gave it to Yale College not long after John died. Klara never mentioned what she did but without her it would never have happened and you would have to take your chances over whether to take a coat with you.

Dr Chien-Shiung Wu

Born 1912 in Shanghai, China and was the middle of three children with two brothers. Her father founded Mingde Women’s Vocational Continuing School because he believed in girls’ right to an education.

Instrumental role in the Manhattan Project, experimental physics and particle physics. Her work on the latter was not given the due credit it deserved when they awarded her the Nobel Prize in Physics.

Wu graduated National Central University of Nanking in 1934 and took a post in a physics lab under female mentor Dr. Jing-Wei Gu who encouraged her to finish her education in America. In 1936 Wu’s uncle provided financial assistance which enable Wu sailed to San Francisco and enrolled at University of California Berkeley. Ernest Lawrence served as her mentor and guide who won the Nobel Prize for Physics for his invention of the cyclotron particle accelerator in 1939. A year later Wu earned her physics doctorate.

By 1942 and without family members present because of the Pacific-based conflicts Wu married Luke Chia-Liu Yuan with their son Vincent joining them 5 years later. They returned to visit China as a family in 1973 they found out that most of their family had been killed in the Chinese Revolution and burial sites of both her parents had been desecrated. They upped sticks and moved to Smith College, Northampton, Massachusetts and New Jersey’s Princeton University. During World War II Wu joined the Manhattan Project at Columbia University. This was US Army’s secret project to develop the atomic bomb where Wu focused efforts on making increasing accuracy with Geiger counters picked up radiation and large amounts of uranium enrichment.

The Yuan family returned to Columbia University with Dr Wu in 1958 she received full professorship then in 1973 upon their return from China was made Michael I. Pupin Physics Professor. Columbia University also made another progressive step in raising her salary to the same level as fellow male employees. Nicknamed “First Lady of Physics” Wu confirmed Enrico Fermi’s beta decay theory of 1933. She worked on Physics’ Law of Parity in atomic science which led to her two of male colleagues winning the Nobel Prize in 1957 but Wu wasn’t recognized. Wu designed and carried out the experiments (known as the Wu experiments) in the National Bureau of Standards laboratories in Washington DC. She also crossed over into the realms of biology and medicine to study red blood cells at molecular levels change to cause sickle-cell most common in people of color.

Though the Nobel Prize committee did not repair their mistake, Wu was not short of honors throughout her career. The National Academy of Sciences elected Wu their 7th woman in 1958 as well as their Comstock Prize in Physics; The American Physical Society’s first female president in 1975; the Wolf Prize in Physics’ first winner and Princeton’s first female honorary doctorate. In 1990, the Chinese Academy of Sciences an asteroid was named 2752 Wu Chien-Shuing after her. In 1995 Tsung-Dao Lee, Chen Ning Yang, Samuel C.C. Ting and Yuan T. Lee set up Wu Chien-Shiung Education Foundation in Taiwan providing scholarships to young scientist.

Wu retired in 1981 from Columbia University after a 47-year career and dedicated the rest of her life to STEM education for girls in China, Taiwan and America. Wu died of a stroke in 1997 in NYC and her ashes returned to China to be buried in Mingde School courtyard then 5 years later Wu was commemorated with a bronze statue. A year later she was posthumously inducted into the American National Women’s Hall of Fame.

Dr. Sister Mary Kenneth Keller

Born December 17 1913 in Cleveland, Ohio as Evelyn Marie Keller later changed her name when she joined the ‘Sister of Charity’ to be a Roman Catholic nun in 1932. In 1940 Sister Mary Keller professed her vows as a nun.

She was also keen to go to university and graduated from DePaul University, Chicago with a Bachelor of Science then a Masters both in mathematics. In 1958 Keller started at the National Science Foundation workshop in the computer science department at Dartmouth College. At the time it was an all-male school and she teamed up with 2 other scientists to develop BASIC computer programming language explaining “information is of no use unless it’s available.”

In 1965 Keller was the first woman to earn a PhD in computer science from University of Wisconsin where she wrote her thesis on “Inductive Inference on Computer Generated Patterns” under the tutelage and mentorship of Professor Preston Hammer. Keller set up Association Supporting Computer Users in Education marked by a technology. She developed a computer science department in a catholic college for women called Clarke College. She chaired the department for 20 years and advocated women in computer science.

Dr Keller supported working mothers by encouraging them to bring their children to class with them. Clarke College in Dubuque, Iowa later renamed Clarke University established Mary Keller Computer Science Scholarship in her name. We have Keller to thank for bringing computers to a mainstream audience across the globe.

Although Dr Keller died in 1985 the impact she had is still widely felt especially at the University of Wisconsin-Madison where the Wisconsin Computing Idea was developed in 2018 “That computing is critical to our university and the state, that UW-Madison will take decisive and bold actions to lead the computing revolution, and that advances in computing on this campus will benefit all corners of this great state.”

Dr Frances Kathleen Oldham Kelsey

Born in 1915 on Vancouver Island, British Columbia.

Frances Oldham graduated with both bachelor and Master of Science degrees from Montreal’s McGill University in 1934 and 1935 respectively. She headed off to the University of Chicago to earn her PhD followed by 12 years of teaching. During which time she met and married a fellow staff member Dr Fremont Ellis Kelsey in 1943 and two daughters arrived as Dr Kelsey completed her medical degree at University of Chicago’s Medical School.

The American Medical Association appointed Dr Kelsey as their editorial associate then to the University of South Dakota teaching pharmacology for three years until 1957 and then a general practitioner until 1960 when she went to work for the FDA in Washington DC. It was there that she made a name for herself first as the Chief of New Drugs Division, Direction of the Scientific Investigations Division and deputy for Scientific and Medical Affairs, Office of Compliance.

Within her first month the FDA understood quickly that Dr Kelsey was not easily fooled making her position against a triple whammy of poor testing, corporate pressure and the release of thalidomide abundantly clear. It had been previously prescribed as a sleeping pill later proven to have caused birth deformities in Europe predominantly Germany and United Kingdom. It was Dr Helen Taussig who testified before the Senate that enabled Kelsey to ban thalidomide from use in the United States. 4000 European children faced serious repercussions but thanks to Kelsey’s timely intervention a similar catastrophe was avoided across the pond.

Dr Kelsey was the second woman to receive the President’s Award for Distinguished Federal Civilian Service for what she did at the FDA from President John F. Kennedy in 1962. He said of her achievement: “… Through high ability and steadfast confidence in her professional decision she has made an outstanding contribution to the protection of the health of the American people.”

Dr Kelsey continued with her contributions towards writing and implementing FDA drug regulation laws to protect all patients who take part in drug trials and investigations. All drugs are now required to demonstrate their safety and effectiveness, consent from the patient to undergo trials and all reactions that are not the expected uniform response to be brought to the attention of and recorded at the FDA.

Beyond the Presidential Honor, Dr Kelsey was honored by Mill Bay, British Columbia with the Secondary School named ‘Frances Kelsey Secondary School’. The National Women’s Hall of Fame inducted Dr Kelsey in 2000 and a year later aged 87 she was the American Medical Association’s Virtual Mentor.

She died in 2015 aged 101.

Hedy Lamarr

Born Hedwig Eva Kiesler on November 9th 1914, Vienna, Austria to a bank director father and concert pianist mother. Hedy grew up an only child and spent a lot of her childhood with her father who encouraged her to be open-minded about the world and while walking together would talk in depth about different machinery. This led to five-year-old Hedy constructing and reconstructing her music box to see how the system worked. Conversely, Hedy’s mother taught her about the arts by sending her to ballet and piano lessons from an early age.

As Hedy grew up, everyone ignored her scientific mind because they were too easily distracted by her looks. Aged 16, she was discovered by film director Max Reinhardt who took her off to Berlin to study acting and gave Hedy her first film role. She met and married Fritz Mandl, an Austrian munitions dealer, who made her life uncomfortable, treated her like his puppet and trapped her into the marriage like a caged bird. She fled her marriage to Mandl ending up in the bright lights of London armed with the knowledge she had gained about weapons of war due to his nefarious associations with members of the Nazi Party.

In London she met MGM Studios’ Louis B. Mayer who became Hedy’s ticket to Hollywood. Hedy hypnotized Hollywood and all who were a part of it’s glamorous scene including quirky businessman and pilot Howard Hughes who was herself intrigued by his pursuit of innovation. He was different because Hedy’s curiosity mirrored his own. He gifted her a small equipment set she kept on her inventing table she worked on in between takes. Together they visited aeronautical manufacturers to introduce her to those involved in the whole process as well as discuss how planes were put together. Hughes was determined to make the fastest planes for military use. Hedy researched and read up on the fastest animals in the world buying books on birds and fish. She studied birds wingspans and fish fins then designed wings for Hughes who when he saw them called her a genius.

She upgraded a stoplight and invented a soda-like tablet dissolvable in water. As history tells us, the best was yet to come for Hedy. At a dinner party in 1940, Hedy met George Antheil who shared similarities with Hughes in his outlook. Hedy was determined to do her bit for the world during the war and put her wealth to good use and this was where she put her munitions knowledge where it was needed.

In 1942, Hedy developed idea for secret communication system to set the course for radio-guided torpedoes using frequency hopping which offered protection to Allied radio waves and maximum accuracy on the target. Hedy and George set about looking for military support and a patent to protect their invention duly awarded in August 1942 the military-grade technology wasn’t used. Hedy used her celebrity status to sell war bonds instead and in 1953 was granted American citizenship.

Unfortunately, the patent expired before Hedy and George earned anything from it. In typical fashion like other female scientists, Hedy’s scientific contributions were only acknowledged towards the end of her life with the Pioneer Award in 1997 from the Electronic Frontier Foundation and the Invention Convention’s Bulbie Gnass Spirit of Achievement Award’s first female recipient.

She died in 2000 and posthumously inducted for her work on “frequency hopping” into the National Inventors Hall of Fame in 2014.

Dr. Mollie Orshansky

Born 9th January 1915 in the Bronx, NYC as the 3rd of 6 daughters.

Economist and statistician.

Her parents were Ukrainian Jewish immigrants who had known and understood poverty. Later Dr Orshansky said she didn’t need to use her imagination as she could remember it well.

In 1931, Dr Orshansky graduated from Hunter College High School, Manhattan and 4 years later with a mathematics and statistics degree from Hunter College. She went to the American University in Washington DC to complete her graduate studied before moving onto the Department of Agriculture Graduate School to finish her studies in economics and statistics.

At the outbreak of the Second World War Orshansky took up a post at the Federal Children’s Bureau as a research clerk analyzing children’s health, growth and nutritional needs. She developed the pneumonia treatment and incidence survey for New York City Department of Health. She spent 13 years at the US Department of Agriculture as a family and food economist and Director of the program’s Statistics Division recording household expenditures and food intake.

Orshansky attended and testified at a poll tax hearing called by the Justice Department. The tax had prevented voting by African Americans and her input led to it’s eradication with her saying that the cost of the tax would be better spent on providing enough food for an entire family’s meals in a day than starving them of it.

Orshansky provided guidelines that now form America’s governmental statistical policy on poverty and assess new policies impact on the poorest citizens by calculating a living expense cost for various sized families on the cheapest nutritional diet.

In 1965, the Office of Economic Opportunity adopted the “Orshansky index” which was never intended to be used as part of a policy instead of a research tool. With food expenses a smaller percentage of the overall household outgoings the guidelines are now out of date.

Social Security Administration and pioneered the government’s definition of poverty for which she received a Distinguished Service Award in recognition. She was also honored by the Social Security, the American Statistical Association and the American Political Science Association.

She died in 2006 in Manhattan after a 6 year legal battle over her care between her family and a Washington judge who argued that Orshansky’s family couldn’t care for her properly after a fall led to hospitalization in 2001 and insisted the economist remain in Washington. This was overturned when the District Court of Columbia Court of Appeals found that the judge had abused her authority.

Dr. Ruth Mary Rogan Benerito

American chemist and bioproduct pioneer born 12th January 1916, New Orleans. Benerito is considered the one who saved the cotton industry with her invention of wrinkle-free cotton with the use of organic chemicals. The process is known today as ‘Wash and Wear Cotton’.

Aged 14 she graduated high school. Aged 15 she enrolled at H. Sophie Newcomb Memorial College of Tulane University graduating in the Great Depression era. She was determined to undertake a research despite employment at an all-time historic low but took a teaching job at a high school west of New Orleans in Jefferson Parish. She taught science, mathematics and driving (Benerito had never driven a car). She used the job to pay her way through night classes while earning her Master’s at Tulane University. She continued to teach during the Second World War then went to the University of Chicago to earn her PhD in Physical Chemistry.

Benerito went to New Orleans to work at the US Department of Agriculture (USDA) Southern Regional Research Laboratories with her husband Frank Benerito. She spent much of her career there and acquiring 55 patents to her name. The wounded soldiers who returned from the Korean War who couldn’t stomach eating inspired her to create a means of getting fats into them intravenously. This process is known today as ‘Total Parenteral Nutrition’ providing all the nutrition people need intravenous solution.

Benerito focused on what led to her breakthrough wrinkle-free, stain-free and flame-retardant with chemically joining cellulose molecules in cotton fibers. She discovered that it was the hydrogen bonds that weakened cotton and increased the likelihood of the material crinkling. The shorten organic molecules added to the fabric were set apart like ladder rungs that stopped wrinkles. She was given the title of “Queen of Cotton” but refused to take credit for the invention stating “I don’t like it to be said that I invented wash-wear, because there were any number of people working on it, and there are various processes by which you give cotton those properties.”

In 1986, Benerito retired from USDA but carried on teaching. Towards the end of her career, she taught part-time university courses at Tulane University and University of New Orleans for 11 years demonstrating her commitment to training the next generation of scientists. She received Lemelson-MIT Lifetime Achievement Award for her contributions to the textile industry and commitment to education.

She died in 2013 aged 97.

Katherine Johnson

Born August 26th 1918, West Virginia and was a NASA scientist.

Johnson was intellectually curious and simultaneously unstoppable number cruncher launched her through grade school. By her teens, she was in high school on the West Virginia State College campus then enrolled at the College when she was 18. She was mentored by her mathematics professor and 3rd African American to have a Mathematics PhD Dr W. W. Schieffelin Claytor. Johnson made short work of her mathematics studies and graduated in 1937 with a Bachelor of Science in Mathematics and French and the highest honors.

Johnson’s first job was as a teacher in a black public school in Virginia but still wanted to do more than just teach. Dr. John W. Davis, the President of West Virginia’s State graduate college, chose Johnson and two male candidates to attend its now integrated schools. She left her teaching job and joined the mathematics program. By the end of it she had decided to leave the school and start a family with her first husband James Goble. When her three daughters were older Johnson returned to teaching.

In 1952, one of Johnson’s relatives informed her about open positions at the all-black West Area Computing Section at the National Advisory Committee of Aeronautics (NACA) laboratory and charge of the laboratory was Dorothy Vaughan. Johnson and Goble moved their entire family to Newport News, Virginia and she started working at NACA’s Langley lab during the summer of 1953.

Dorothy Vaughan transferred Johnson to the Flight Research Division’s Maneuver Loads Branch after just two weeks but came as no surprise when the position was made permanent. Over the course of four years, Johnson analyzed flight test data and investigated a wake turbulence that caused a plane crash. At the end of the job in December 1956, James Goble passed away from cancer.

1957 was the year that made American space history but also changed Johnson’s and her colleagues’ lives. ‘Notes on Space Technology’ were lectures given by engineers in Flight Research Division and Pilotless Aircraft Research Division held in 1958 and Johnson contributed some of the mathematics for the accompany document. These engineers formed the Space Task Group who worked towards astronautical travel as we know it. Johnson was an integral part of the team and was there when NACA became NASA completing trajectory analysis for the Freedom 7 mission in May 1961 led by Alan Shepard and America’s very first attempt to reach space.

Johnson and Ted Skopinski co-wrote ‘Determination of Azimuth Angle at Burnout for Placing a Satellite Over a Selected Earth Position’ a report that determined whether it was safe for rockets to go before take-off by manually running the equations through a machine. This report marked a major milestone for the Flight Research Division when they gave Johnson author credits. She co-authored 26 research report providing mathematical equations for machines across her career.

Thus began Johnson’s journey to the household name in the book and film “Hidden Figures” in 1962 with the preparation of John Glenn’s orbital mission. It was Glenn who wholeheartedly put his trust in Johnson’s mathematical skills and cunning “If she says they’re good then I’m ready to go.” Other astronauts weren’t quite so easily trusting in systems prone to cutting out and switching off. A worldwide communications network was set up with connected tracking stations and computers in Washington, Cape Canaveral in Florida and Bermuda with the power to control the rocket from take off to landing. It was Johnson’s job to crunch the numbers through her mechanical calculating machine that had been through the computers. The success of John Glenn’s space launch was the turning point asserting America’s place in the space race.

Johnson always said that her greatest involvement were the calculations produced for Apollo’s Lunar Module to sync with the Command and Service Module around the Moon as well as the Space Shuttle and the-now Landsat (then called ERTS: Earth Resources Technology Satellite).

In 1986, after 33 years at Langley, Johnson retired despite the sheer love for her job.

She was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 2015 aged 97 by President Barack Obama. Her role at NASA is depicted in the phenomenal 2016 book and film ‘Hidden Figures’. If you haven’t read the book or seen the movie then we would highly recommend you go do that.

She died in 2020.

Dr. Dorothy Lavinia Brown

Born 1919 in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania to an unmarried mother and put up for adoption at the white Troy Orphan Asylum (now Vanderhyden Hall) aged only 5 months. As a child Brown had immeasurable talent and her curiosity in medicine peaked when 5-year-old Brown had a tonsillectomy.

Brown and her mother had a testing relationship. At 13 years old Brown’s mother Edna returned for her and Brown would run away from her mother’s home to the orphanage 5 times. Brown had several jobs as a teenager to help pay her way working in a Chinese launderette and mother’s helper amongst others. It was the latter job for a Mrs W.F. Jarrett that pushed Brown into becoming a physician and aged 15 enrolled herself at Troy High School.

The principal searched for a foster home for Brown to go home to and introduced her to the most influential people in her life: Lola and Samuel Wesley Redmon who provided her with the safety and security she had craved. It was with their help that Brown graduated high school at the top of the class in 1937 and the Troy Conference Methodist Women awarded a 4-year scholarship which took her to Bennett College in Greensboro, North Carolina.

Brown worked for the Army Ordnance Department as an inspector in Rochester, New York in the Second World War. In 1944, Brown went to Nashville, Tennessee enrolling at the Meharry Medical College to study medicine and graduated in 1948. She spent a year at Harlem Hospital, NYC as a resident intern to do a 5-year residency at Meharry’s George Hubbard Hospital. In 1955, she became a Surgery Professor.

It was also around this time that Brown had to make a huge life-changing decision when an unmarried patient of hers begged Dr Brown to adopt her newborn daughter. She also made history as the first unmarried woman to adopt a child in the whole of Tennessee in 1956. In tribute to her foster mother, Dr Brown named the girl Lola Denise Brown.

From 1966 to 1968 Brown introduced a bill reform allowing legalized abortions resulting from incest and rape whilst serving in the Tennessee House of Representatives. At the time it was controversial and highly contested but when it came down to the vote it was 2 votes short to be successful in passing. Dr Brown did not stop there helping to finance what is now known as Black History Month but then called Negro History Week.

Between 1959 to 1983, Dr Brown remained in Nashville for the rest of her life and served as Chief of Surgery at Nashville Riverside Hospital and at Meharry’s Clinical Professor of Surgery. In 1982, Dr Brown was a consultant to the National Institutes of Health.

In 1970, Meharry Medical College Women’s Residence was named after Dr Brown. In 1993, the Carnegie Foundation honored her with the humanitarian award which Dr Brown accepted on behalf of all women, children and healthcare. A year later Dr Brown was given the Horatio Alger Award.

Dr Brown died of congestive heart failure aged 85 on June 13th 2004.

Marie Maynard Daly

Born in 1921 Queens, NYC who made breakthroughs in cholesterol studies and how it affects the heart’s ability to work; the nutritious and harmful elements’ effects on arteries as well as elderly age and hypertension on the heart’s ability to pump blood around the body.

Marie grew up loving books and her favorite was ‘The Microbe Hunters’ by Paul De Kruif. Her father had pursued a chemistry bachelor’s degree at Cornell University but due to financial reasons could not continue. She inherited his love for the sciences and when she arrived at Hunter College High School her scientific aspirations were fully endorsed. In 1942, she graduated Queens College in New York while living off-campus with a chemistry bachelor’s degree magna cum laude. She was offered a fellowship to continue her chemistry graduate studies at NYU alongside her part-time job as a lab assistant at Queens College. She completed her master’s degree in a year.

Daly went to Columbia to a PhD in Chemistry. She had spent the previous year at Queen’s College teaching Chemistry students with enough finance from the university to help pay her way through her studies. Mary L. Caldwell who studied amylase, a digestive enzyme, was a mentor to Daly who analyzed and studied compounds made in the body are affected by and become digested by the body. She called her thesis “A Study of the Products Formed by the Action of Pancreatic Amylase on Corn Starch.” After 3 years at Columbia University, Daly became the first African American woman in the United States awarded a PhD in chemistry from Columbia University in 1947.

She moved to Howard University in Washington to teach for 2 years. The American Cancer Society gave Daly a grant for further research working alongside a molecular biologist extraordinaire Alfred E. Mirsky at the Rockefeller Institute, NYC. For 7 years, Daly worked on how parts of the cell nucleus structure works and absorbs what we put in our bodies studying among other things the effects of cigarette smoking on the lungs. She taught at the College of Physicians and Surgeons of Columbia University in biochemistry. Her last job before retirement in 1986 was at the Albert Einstein College of Medicine as a Professor.

Like many women of color in her generation and position, Daly wanted to get more minority students into STEM programs so she set up a scholarship fund in her father’s memory for African American students studying science at Queens College.

She died in 2003

Jewel Plummer Cobb

Born 1924 in Chicago, Illinois.

It was hardly a surprise to her family when Cobb became a cell biologist and cancer researcher. Her family were full of medical practitioners that trickled down the generations with her grandfather a Howard College Pharmacy degree graduate and freed slave then to her physician father. Her mother collaborated with the Works Projects Administration as a dance schoolteacher. Cobb spent a lot of her early childhood in her fathers home library full of scientific journals, magazines, newspapers and books telling African American stories and achievements.

She grew up in the racial segregation era of Jim Crow laws that meant there weren’t uniform standards across schooling. Cobb refused to let this stop her and it was during a biology class in high school where Cobb fell in love with the subject. Unfortunately, Cobb did not stay for long at the University of Michigan after graduating high school due to racial discrimination. She moved to Talladega College in Alabama (a black traditional institution) where she graduated with a Bachelor of Science degree in Biology.

Cobb had her initial application rejected from New York University on the grounds that she was black. Cobb was resolute in the face of their racist attitudes and went to the University to showcase her qualifications and prove she was as deserving to be there as her white counterparts. New York University soon changed their minds and offered her the job. Cobb started her teaching job in 1945 and earned her Master of Sciences degree in cell physiology in 1947 then her PhD in 1950.

After graduating, Cobb worked in cancer research focusing on how melanin (the pigment in our skin) changes into melanoma. This breakthrough work was awarded by the National Cancer Institute who made her a fellow. She returned to Illinois to be the University of Illinois’ Director of Tissue Culture Laboratory before returning to her teaching-researching career at NYU, Hunter College and Sarah Lawrence College.

Cobb’s passion for cancer research led her to studying how chemotherapy affects cancerous human cells. This work has enabled cancer research to now find ways to tailor treatment to each patient and treatments targeting cancer at its source before it has chance to spread.

In 1967, Cobb became Connecticut College’s Dean and Professor of Zoology whilst providing funding to programs bringing in more women and minorities into STEM fields dominated by white males. She continued in the same vein when she left Connecticut College for Douglas College at Rutgers University. Though Douglas already had female STEM employees Cobb wanted more and introduced a variety of new programs. In her 1979 article “Filters for Women in Science”, Cobb wrote in detail about all discrimination women faced in their academic careers and professional work life fundamentally destroyed all hope of them having successful STEM careers. She fought for accessible STEM education and career opportunities for all women and minorities despite all she faced as a black woman. She always found a way to provide funds even if public or private channels ran out because Cobb’s staunch view education led to success.

In 1981, California State University named Cobb as their President during which she acquired financial help to invest in STEM infrastructure (including new facilities) and an apartment complex to house its students. She also started a program tailored just to minority students studying mathematics mentored by faculty teams to help achieve higher marks.

Though Cobb retired in 1991 she continued serving as a trustee on multiple boards and still campaigned for female and minority rights to better STEM education and opportunities. She was honored with over 20 honorary degrees and countless awards. In 1993, the National Academy of Science gave her the Lifetime Achievement Award. In 1999, Cobb was selected by The Center for Excellent to be awarded with the Achievement in Excellence Award. For her outstanding contribution to educational diversity, Cobb was the first Reginald Wilson Award’ winner.

She died in 2017.

Evelyn Boyd Granville

Born in 1924 and was an American mathematician, computer scientist and teacher. Boyd grew up in Washington D.C. and the Great Depression in the midst of segregation. She attended Dunbar High School and was taught by white and black educated teachers that gave her the impression that education was for all and means of obtaining gainful employment. She saved pennies, requested financial help and academic scholarship to get herself through school.

Boyd was 1 of 5 valedictorians and graduated with a Bachelor’s from Smith College. In 1949, she was the Second African-American woman to earn a mathematics and double master’s degree and doctorate in America from Yale University. Dr Boyd taught at Fisk University in Nashville which was an all-black college, California State University and Texas College in Tyler where she taught mathematics and computer science. In Texas, Dr Boyd and her husband cared for and raised chickens selling their eggs.

She calculated the launch times for satellites during the space race and part of the team contributing to NASA’s Vanguard and Mercury. Her computer programmer role at IBM meant studying and improving formula methods for rocket trajectories and orbit computation. In 1967 Dr Boyd returned to complete a 3-decade teaching career promoting the benefits of education. Dr Boyd retired in 1997 and carried on teaching students how important Mathematics was. She was also on the speaker circuit carrying out talks on behalf of associations who requested her participation.

In 2019 at the Annual National of Mathematicians Banquet awarded Dr Boyd aged 94. Dr Granville was the first African American to be awarded an honorary doctorate in mathematics from Smith College. She also has honorary doctorates from Spelman College, Yale University and Lincoln University.

Elsie Shutt

Born in 1928 in New York but grew up in Baltimore as the only child.

Elsie lost her father, a Ford car salesman, at the age of four. Her mother was a chemistry major who took up a lab technician role at Johns Hopkins University whilst her daughter was at school.

Science came to Elsie a lot easier than English or Literature and it was a given that she would attend Goucher college but had free rein over choosing what she wanted to specialize in. She eventually settled on Mathematics and Chemistry major because she loved logic more than chemistry. Earned a graduate fellowship from Pepsi-Cola to go to Radcliffe. She graduated college 18 months before everyone else which she didn’t find all that unusual at the time.

When the fellowship from Pepsi-Cola ended she took up a teaching fellowship. Radcliffe allowed men to teach women but not the other way around. Shutt was the second female to be the remedial mathematics teaching fellow at Harvard after Lisl Novak who had the role during the Second World War. She was one of four or five other female graduates but only one of two doctorate students. She wanted to be a college mathematics teacher. Interviewed at Aberdeen Proving Ground in Maryland and shown the ENIAC computer because the government were sourcing mathematics majors. It was there at the APG Shutt learned her coding craft, a military facility and spent three summer terms working on ORDVAC coding while she was at college.

In 1953 Shutt took time away from graduate school and was employed by Raytheon where her mentor Dr. Richard Clippinger worked with complete gender parity aside from when it came to having a child. She remained at grad school then applied for Fulbright was accepted and then went to Nancy, France for a year to learn from a group of distinguished French mathematicians who hid from the Nazis under a nom-de-plume “Nicholas Bourbaki”. Since the end of the war they had separated and moved to different places. : Shutt and her husband returned home to Raytheon working on programming SC-101 without touching the machine until everything was ready.

In 1957 Shutt gave birth and state law demanded that she resign from her post and the firm didn’t offer part-time work no matter how good female coders were. Shutt never wallowed instead she founded her own company Computations Incorporated that offered work to at-home mothers including part-time and trained them all up just as she had been. Mothers looked after their kids during the day and then worked at night renting local computers.

In a 1963 Business Week Shutt’s employees labelled as “the pregnant programmers” in an article titled “Mixing Math and Motherhood”. In 1967 “The Computer Girls” were written about because of the sheer number of female programmers employed in the industry showing them with the iconic beehive look working on computers. It was a job that could earn $20k equating to more than $150k in today’s money and the only one where women were able to thrive. Other mathematics related careers involved teaching or working at insurance firms completing typical calculations.

Dr Gladys West

Born 1930 in Sutherland, Virginia.

Dr West was responsible for making mathematical breakthroughs and programmed all mathematical calculations in the Global Positioning System (GPS) breakthrough. She contributed to programming the IBM 7030 ‘Stretch’ computer improving calculations for what became the GPS.

She contributed to discoveries in outer space at the US Naval Weapons Laboratory concerning planets in the solar system including Earth.

Has been inducted into Air Force Space and Missile Pioneers Hall of Fame.

Elizabeth Feinler

Born 1931, West Virginia. Original nickname was ‘Betty Jo’ but when her younger sister said her name it sounded like Baby Jake and the name ‘Jake’ stuck. She was the First person in her family to attend university. She graduated from West Liberty State College age 20 earlier than her classmates before working towards a PhD in Biochemistry.

Jake discovered a love for data compilations in her part-time job and never completed her PhD. Between 1972-1989: Director of Network Information Systems Centre at Stanford Research Institute. The institute oversaw internet addresses and web domains. In the late 1980s helped to transition to domain name systems and domain name protocols which built the internet.

Annie Easley

Born in 1933 Birmingham, Alabama.

Easley attended Xavier University majoring in Pharmacy for 2 years. When she had finished university, met her husband and moved to Cleveland to start her career as a human computer in 1950s. Essentially the role of human computers was computations by hand for researchers.

Worked as a computer programmer supporting then NACA (now NASA). There wasn’t a pharmaceutical school nearby so she applied for a job at National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA) and started her job a fortnight later. She was one of four African Americans who developed and implemented code leading to development of batteries used in hybrid cars. Throughout her career Easley was instrumental in encouraging women of colour to get into STEM careers.

She died in 2011.

Karen Sparck Jones

Born in 1935 in Huddersfield, Yorkshire, UK.

Sparck was responsible for information retrieval and natural language processing the very foundations of web search engines as we know them.

Her university career between 1953-1956 saw Sparck studying history and philosophy at Grinton College, Cambridgeshire. From 1956-9 she worked at the Cambridge Language Research Unit as a researcher use of thesauri for language processing collaborating Roger Needham. Her researched formed her groundbreaking then-futuristic PhD thesis “Synonymy and Semantic Classification.”

In 1958 Sparck married Roger Needham.

In the 1960s Sparck worked on information retrieval (IR) and introduced IDF term ‘weighting’ now a part of web search engines and used in applications that process language. She then began research on NLP whilst still maintaining an interest in IR.

Two decades later contributed to the UK Alvey program by setting up the Intelligent Knowledge Based Systems Research Area (IKBSRA) that provided funding to AI and language projects and carried out heterogeneous information inquiry systems and natural language front ends to databases research.

She set global standards for natural language processing (NPL) overseas including America. Travelled and promoted research carried out by her colleagues as the Alvey Coordinator and President of the Association for Computational Linguistics. She was the first senior computing female expert to give the University of Pennsylvania’s opening Grace Hopper Lecture at the Conference.

She taught PhD students the Philosophy Master’s degree in Computer Speech and Language Processing and the Computer Science Tripos NPL and IR computer speech and languages.

She was awarded: ACM SIGIR Salton Award, the American Society for Information Science and Technology’s Award of Merit, the Association for Computational Linguistics Lifetime Achievement Award, the BCS Lovelace Medal, the ACM-AAAI Allen Newell Award.

She became a Fellow of: the British Academy, the American Association for Artificial Intelligence and European AI.

Both Karen and Roger were sailing enthusiasts.

She died from cancer in 2007.

Margaret Hamilton

Born August 17th 1936 in Paoli, Indiana.

Computer scientist, systems engineer, business owner.

MIT Instrumentation Laboratory’s Software Engineering Division Director responsible for the inflight software that allowed Neil Armstrong, Buzz Aldrin and Michael Collins’s Apollo 11 mission to land on the moon.

Hamilton founded 2 software companies.

2016: Received the Presidential Medal of Freedom from the-then sitting President Barack Obama for her contribution to the successful Apollo 11 mission.

Dr. Virginia Holsinger

March 13th 1937 in Washington, D.C. and was an American chemist

In 1958 Holsinger graduated from College of William & Mary with a Chemistry Bachelor of Science. She put her chemistry degree towards solving food security issues.

Dr Holsinger began career at the USDA’s Agricultural Research Service Dairy Products Laboratory in Washington D.C. In 1959 she joined ACS and became an emeritus member. In 1974 she transferred to USDA’s Eastern Regional Research Center in Wyndmoor PA as Program Lead in Milk and Dairy Foods Chemistry and Technology until retirement in 1999.

1980: Earned a PhD from Ohio State University Food Science and Nutrition then began researching dairy products. With her team she helped develop shelf-stable mixture of whey and soy mix milk-substitute to cater to worldwide food aid programs.

Her work in lactase enzyme research allowed lactose-intolerant digest milk by breaking down disaccharide into galactose and glucose. This breakthrough led to her creating Lactaid products commercially. Her enzyme work was used in enzyme fortification in military food rations.

She analysed the rheological properties for all cheese which contributed to lower fat natural mozzarella cheese. She also developed a dried milk to be used as a shortening ingredient in baking.

In collaboration with Farm Service Agency and US Agency for International Development Holsinger and her team created a grain blend when mixed with water provides nutritious porridge for feeding famine, drought and war victims and their families.

Over 100 scientific papers were written by or co-written by Holsinger and was honoured with awards from agricultural and food chemistry groups. In 1983 she was awarded R&D Associates for Military Food and Packaging Systems’ Col. Rohland A. Isker Award. In 1986 she won ACS Division of Agricultural & Food Chemistry’s Distinguished Service Award. In 1987 the Institute of Food Technologists’ Industrial Achievement Award & USDA Distinguished Service Award for Research bestowed on Dr. Holsinger’s team. In 1992 won Agricultural Research Service’s Distinguished Scientist of the Year Award and in 1995 the National Science Foundation awarded her the Lifetime Achievement Award for Women in Science and Engineering.

In 2000 she was inducted into the ARS Hall of Fame.

She died on 4th September 2009.

Mary Allen Wilkes

Born 1937 in Chicago

Wilkes biggest contribution to STEM was the home office concept and was the first female to have a home PC installed. She had never planned to be a pioneering software engineer instead she wanted to be a civil lawyer. In 8th grade her Geography teacher told Wilkes she’ll be a computer programmer in future but Wilkes had no idea what a computer nor a programmer was. It was entirely alien.

In 1959 Wilkes graduated from Wellesley College with philosophy degree in full knowledge that she would never be able to attain her dream of becoming a lawyer. Even her mentors said as much and even if she was successfully employed she’d never end up in front of a judge but most likely a legal librarian or secretary or estate planning and probate.

She became a Computer programmer because she had remembered her geography teacher telling her that computers were the future. After hearing that MIT had some onsite she made her parents drive her there, showed her face in the school’s employment office regarding computer programming jobs. They confirmed they did and employed her despite not having any experience in writing code. It was of the age where no-one knew about coding, very few colleges ran courses and there weren’t any university degrees that specialized in the subject. 1965 was the year Stanford University had their first computer science department. To measure the candidates, institutions like MIT provided aptitude tests that looked for logical thinking skills. As a result of her degree Wilkes had already been mentally prepared with the use of arguments, inferences and statement like that of written code.

Wilkes worked with IBM computers (IBM 709 & IBM 704) for a year between 1959-1960 but it didn’t turn out the way she wanted it to which meant spending hours pouring over every piece of code to find the mistake. She would envisage herself as the computer to re-write the program which involved writing it all out by hand, hand to a typist to translate into holes on a punch card, carry a box of punch cards to an operator who would then feed them to the machine. The machine would run the program and print out the results. There wasn’t a computer screen nor a keyboard. What was more challenging was there were only 4000 words in the IBM 704’s memory.

It took Wilkes time to become refined, succinct and to the point with coding because it was all a big puzzle. Wilkes was fastidious and a complete perfectionist of her time. MIT labs had a majority workforce of female programmers and across America a quarter of all programmers were women.

In 1961 Wilkes joined digital computer group contributing to LINC development of TX-2 which was the very first PC that could fit in an office or a lab with a keyboard and screen without the need of punch cards and printed reports. It was down to Wilkes to write the software code to allow the user to be in control of the computer in real time.

Men and women’s salaries were not the same, there was sexism and women were not promoted as often as the men were. To Wilkes, being surrounded by those that had the same intellectual capacity that she had topped everything over the problems she had to face. An early model of the working LINC solved a data-processing problem that had a biologist scratching his head and ended up doing a jig around the machine in celebration.

In 1964 Wilkes returned from her global travels and was asked to finish designing and writing the operator manual for the console’s final design. Wilkes had no desire to move to the new lab in St. Louis so the LINC was sent to her parents’ Baltimore home. In 1965 she was the first home computer user. Wilkes’ Episcopal Clergyman father bragged about this to anyone who would listen. The code she had created was used to analyze medical data and invented a chatbot to record and ask patients about any symptoms they had. Computers had been intellectually stimulating but it grew time for Wilkes to pursue her dream of being a lawyer.

She applied to Harvard Law School to study law and post graduation she worked for 4 decades as the lawyer she had always dreamed of being. Aged 81, Wilkes is retired and living in Cambridge, Massachusetts and looks just as she did in the photos of her posing with the LINC. She talks to students studying computer science which currently has less women and has become less welcoming to females than when Wilkes was working.

What surprises her the most? Young coders know extraordinarily little about the women who were the earliest computer pioneers and innovators populating the tech industry. If there was a survey done today the stats would back this up.

Second World War

Calutron Girls

They left their homes and families to join the war effort not knowing what they were about to walk into. The Calutron Girls were brought into operate calutrons using electromagnetic separation isolate enriched uranium for the first nuclear bombs. The biggest surprise of them all was the Manhattan Project which was the secret project culminating in the bombing of Japanese cities Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

Tennessee Eastman Company recruited young women but their typical candidates were high school graduates. Often kept in the dark regarding the real objectives of the project these young women were highly skilled at using the mass spectrometers and made continuous improvements on uranium production to increase accuracy. The girls had higher levels of production than most of the scientists and engineers who just so happened to be male at the facility.

This secured jobs, America’s position in the Second World War and played its part in the outcome of the war. Leadership doubted the capabilities of these women but they soon proved their worth and their contribution to STEM would mean that life might not have made the advancements and positive in-roads to get us to where we are.

Bletchley Park

In the United Kingdom women made up 75% of the workforce of 10,000 people. They could not be referred to as analysts like their male colleagues so had the title of ‘Secretarial’ instead. When mentioning Bletchley Park this is one of the major moments where female STEM figures had their moment of glory but at a cost as they were never given credit.

US Army

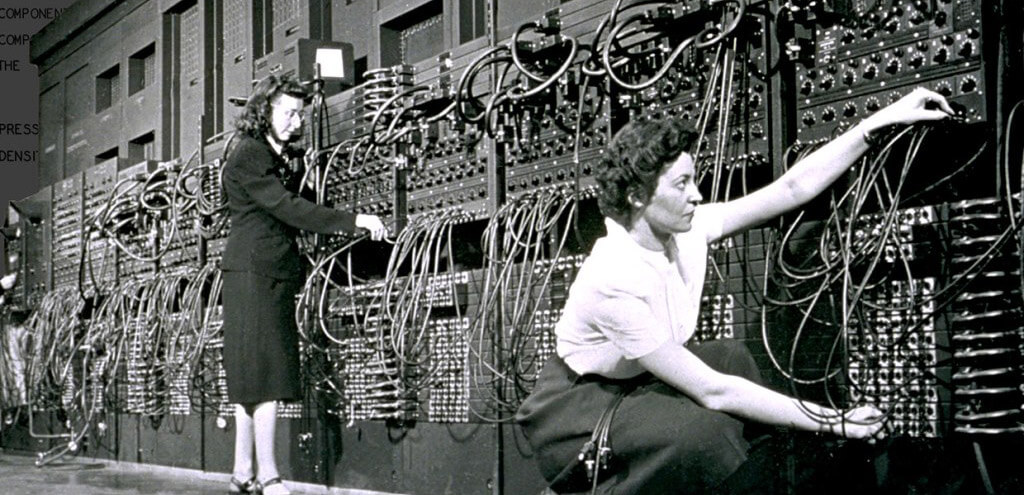

1945 was the year of the computer programmers – all of them women. There were approximately 100 female mathematicians including the ENIAC girls: Kathleen McNulty; Betty Jean Jennings, Frances Bilas; Elizabeth Snyder Holberton; Marlyn Wescoff and Ruth Lichterman.

What was the ENIAC?